Section 1: Introduction

Section 1: Introduction

The West Midlands has fundamental economic advantages.

- Our scale. The West Midlands has the largest population of any city region outside of London, and, at almost twice the size of Oxford and Cambridge combined, it is the third largest economy of all UK city regions at £77 billion.

- Our people. The West Midlands’ population is projected to grow at the second fastest rate of all city regions in the UK, with only London expected to grow more in absolute terms. The West Midlands has the second youngest demography with a median age of 36.6 years and is the second most ethnically diverse city region in the UK. Unlike most other areas, its younger and working-age population is expected to continue to grow over the next 10 to 15 years.

- Our investment and innovation records. Last year Birmingham landed more foreign direct investment than any other UK city outside of London, while the West Midlands has the second highest ratio for leveraging private sector investment in research and development from public funding. On top of this, the region has distinctive economic strengths, high-performing universities, is recognised by the European Union as only one of two regional innovation valleys in the UK and was one of three finalists in the European Capital of Innovation Awards 2024.

- Our connectivity. The West Midlands sits at the very heart of the country and will be better connected to the UK’s capital as a result of HS2 by the mid-2030s. Even today 90% of the UK population is accessible within four hours.

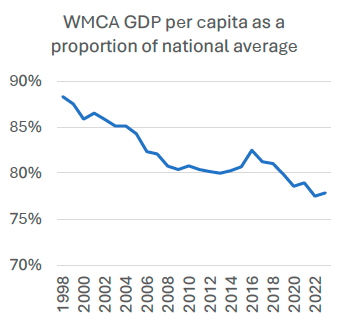

While the West Midlands has strong foundations, it is not yet at its full economic potential. Its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita—a traditional measure of the strength of the economy—in 2022 was £28,841, 22% below the national average, placing the West Midlands 33rd of 40th in a list of comparable regions on this measure. We think the reason the West Midlands is underperforming is because it is trapped in a self-reinforcing low-productivity and low-wage equilibrium that holds down the region’s economy and the living standards of its population.

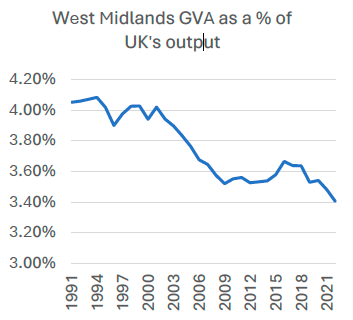

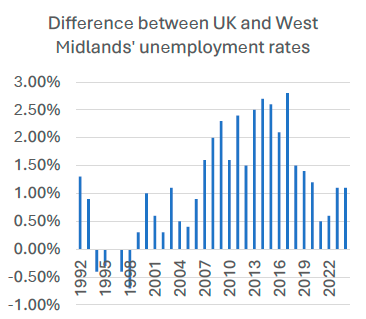

On the first part of this equilibrium —productivity— the average gross value added (GVA) per hour worked in the WMCA area was £34.50 compared with £36.60 in Greater Manchester and the UK average of £39.50. Figure 1 (below) shows how our productivity challenge has been growing over time. On the second—employment—figure 2 (below) shows there has been a consistent gap between national and West Midlands’ employment rates for 30 years. The root cause of the West Midlands’ employment challenge lies in the severity of job losses in its primary industries from the 1980s onwards, which was steeper and more extreme than in any other European region outside of Eastern Europe. Figure 3 (next page) shows the effect of the West Midlands’ low productivity and employment rates in widening the gap between regional and national GDP per capita.

Figure 1: West Midlands' GVA as % of UK's output

Figure 2: Difference between UK and West Midlands' unemployment rates

Figure 3: WMCA GDP per capita as a proportion of national average

These challenges are not unique to the West Midlands. The gap between the most and least productive regions in the UK is as big as in the entire Eurozone. If the UK were divided into two, with one group comprising of London, the South East, the East, the South West and Scotland; and the other group the remaining regions, the first group would have a GVA per capita comparable to Finland, Australia and Canada but the second would have GVA per capita levels below Slovakia, Slovenia and Czechia. More broadly, across 28 economic measures of inequality, the UK is one of the worst among OECD countries.

These economic concepts matter because they determine West Midlands’ residents’ living standards. On average across all seven of the WMCA’s local authority areas, households have less disposable income to spend today than they did in 1997. The social and human consequences of this are significant: the West Midlands has the highest national levels of child and total poverty in the country, at 43% and 27% respectively; lower-than-average life and healthy life expectancies; and residents with fewer qualifications than elsewhere in the country.

However, there are reasons to be optimistic about the region’s future economic transformation, and the ability for the future to look different to the past.

First, as mentioned above the West Midlands has strong economic foundations and distinctive strengths. Second, economic transformation is possible: many regions have achieved it before, and we are learning from them. Indeed, the West Midlands has bolstered a high-performing economy in living memory—gross disposable household income in the region was 13% higher than the national average in 1961—until the national government took steps to deliberately curtail its growth thereafter, showing that policymakers have the ability to generate higher growth in the West Midlands: it has happened before albeit under different circumstances. Third, the region is at the vanguard of English devolution and is gaining more and more powers to be able to shape its destiny, led by local leaders.

There is a compelling case for change from a national perspective. If the West Midlands was as productive as the UK average, the UK economy would be £12 billion larger. The £12 billion boost that would come from making our economy as productive as the UK average is the largest potential productivity boost of any city region economy of the UK. The Centre for Cities calculated that if all regions outside the South East performed in line with relevant international comparators the national economy would be £83 billion—4% larger.

The West Midlands Futures Green Paper that accompanies this report aims to support a conversation across the region to affirm and crystalise our long-term strategic economic priorities as a region to underpin a ten-year programme of economic transformation—rising to the challenges above and detailed below, built upon our foundations and strengths, and in delivered partnership with all those who have a shared stake and role in a more prosperous West Midlands.

One of the key parts of the Green Paper is a theory of growth for the West Midlands, which proposes what needs to change in order to realise the region’s full economic potential. This document is the evidence base that underpins our theory of growth. It is structured as follows.

- Section 2 explains our vision of, and what the West Midlands means by, inclusive growth, which our theory of growth is geared towards realising.

- Section 3 explains our methodology: how we went about developing our theory of growth.

- Section 4 is the main section of the document and sets out our analysis of the West Midlands economic system through the lens of 12 ‘sub-systems’. For each sub-system, we present a hypothesis that captures the essence of the challenge and/or opportunity that our theory of growth needs to prioritise responding to, if we are to achieve economic transformation.

- Section 5 stands back from each sub-system and suggests how, looking across them all, we could take our analysis further by prioritising our priorities.