Section 4.1: Economic Geography and Polycentricity

Hypothesis:

The West Midlands may sufer lower productivity on account of its morphological polycentricity relative to London or Manchester—we have less ‘agglomeration’. But if it can enhance the functional integration between and harness the complementary roles of its cities and boroughs, recognising the signifcance of Birmingham, it may have a ‘goldilocks’ combination of scale, location and spread for quality o f life and inclusive growth.

We understand the West Midlands to be a polycentric region. This matters, because our spatial structure has implications for our economic performance and strategy.

Morphological polycentricity: how people, jobs and economic activities are spatially distributed across the region

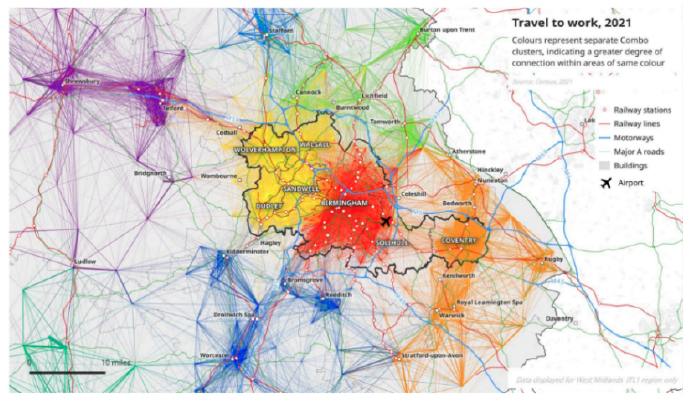

Figure 6: Travel to work 2021

The West Midlands is comprised of three distinctive functional economic areas each with their own ‘gravitational pull’, a key feature of our polycentricity. These are, broadly speaking, the Black Country (yellow); Birmingham, with strong links into Sandwell and North Solihull (red); and Coventry, with strong links into Warwickshire (orange). The map to the left visualises these three functional economic areas, based on labour market data.

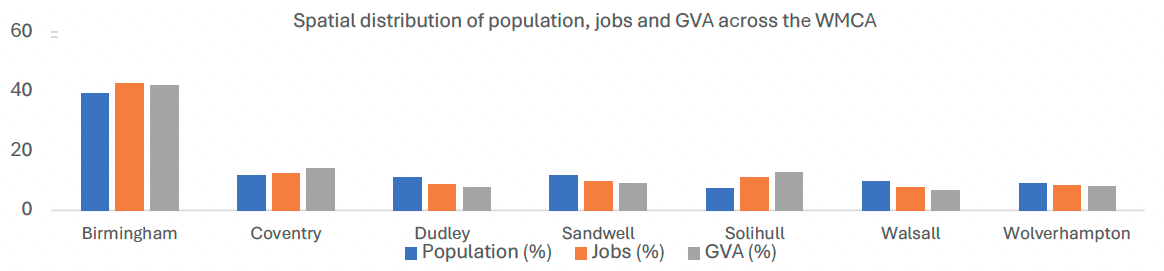

However, not all of our three strategic centres are of the same size. Looking at the distribution of jobs, GVA and population across the WMCA area (Figure 4, below), Birmingham is 43%, 42% and 39% of the WMCA area economy. In essence, looking at our morphological geography, we have traits of being both polycentric—because we have three internal functional economic areas—and monocentric—because of the size of Birmingham.

Figure 7: Spatial distribution of populations, jobs and GVA across the WMCA

This matters because, on balance, the evidence suggests that morphologically polycentric regions generally do not perform as well economically as morphologically monocentric regions. While this could be seen as an economic disadvantage for the West Midlands, there are a number of potential advantages of polycentricity that, if intentionally harnessed as part of our economic strategy, could be a source of future strength. For example, monocentric growth tends to push dense development into the single urban core, whereas polycentric regions can channel growth into multiple nodes, to reduce some of the negative costs associated with agglomeration and create a more diverse work, live and leisure ‘ofFer’ to residents. This is why polycentric regions are often associated with lower housing costs and better housing quality due to reduced pressure on a single urban core, helping to reduce inequalities. In addition, because of multi-directional travel fows and more localised travel, polycentric regions tend to have less congested traffic. Other analyses have suggested that polycentric structures are better able to enhance quality of life by improving access to essential services, ultimately leading to greater life satisfaction.

Functional polycentricity. While the West Midlands cannot change its morphology—the spatial distribution of people, jobs and economic activities—it can afect another dimension of polycentricity: functional polycentricity. Functional polycentricity refers to the integration and connectivity between the cities and boroughs of a region. Looking at commuting fows across the region, for example, the latest data—collected during Covid-19 so likely to be an underestimate—suggests that over 200,000 people, or 17% of the WMCA area’s workforce, live in one part of the region but work in another. Around 70,000 of these cross-border workers travel into Birmingham. Compared to other areas, the West Midlands is ‘mid-table’ in terms of functional integration: in Greater London, some 26% of its workforce lives and works in diferent parts of the city region. Compared to polycentric regions overseas, the level of functional integration is lower still. In other polycentric regions such as the Randstad region of the Netherlands and Rhine-Main region of Germany, cross-border working represented some 50% and 63% of the workforce, respectively, of their largest cities. A particular characteristic of successful functional polycentric city region is the use of mass transit system, including train, tram, bus and metro, and the strengthen of connectivity between places.

Cross-border commuting is just one lens on functional polycentricity. There are cross-border fows of people moving around the region for leisure and culture activity, housing markets and patterns of consumption. Another way to look at functional polycentricity is to consider the diferent, complementary economic specialisms and strengths of diferent parts of the region. This is apparent both when we look at places’ economic strengths, as well as the ability for transport connectivity and housing to link people from one part of the region to jobs in another.

This matters to the West Midlands because, the evidence suggests, more functionally polycentric regions perform better economically. Functional integration is the key determinant of whether a polycentric region actually functions as an interconnected economic unit. Whereas nothing can be done about the West Midlands’ morphological polycentricity, except for harnessing the advantages, the West Midlands as the ability to promote functional polycentricity and realise the complementary strengths and specialisms of our cities and broughs. This is the basis of our central hypothesis.

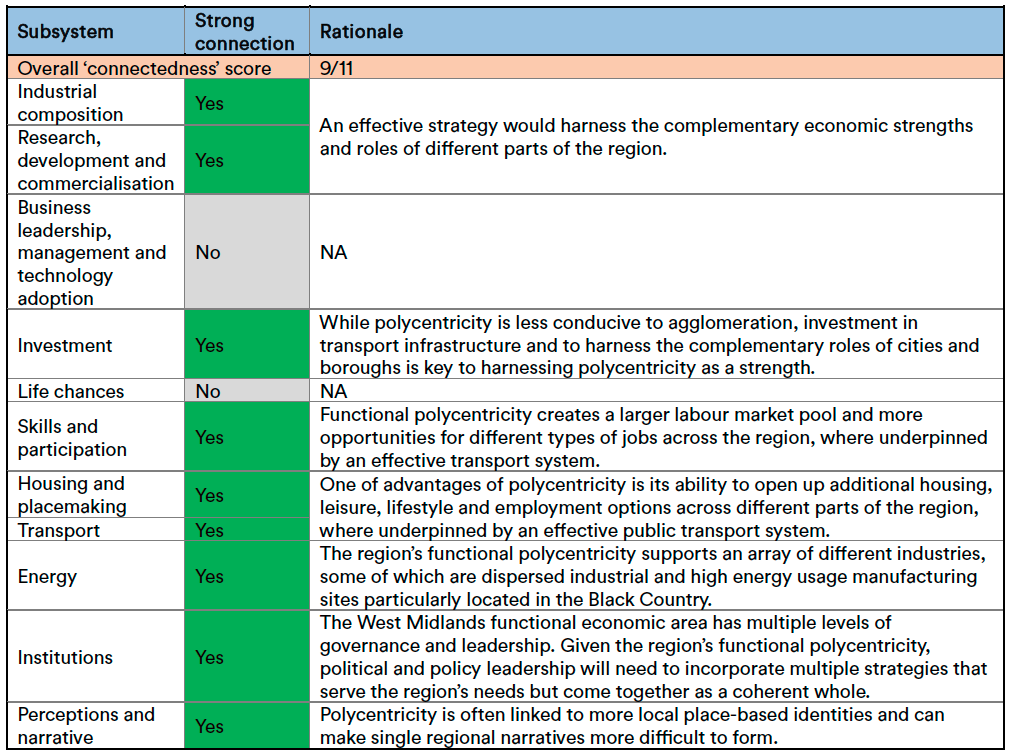

Connections with other sub-systems

Our polycentricity hypothesis has implications for several other sections of our theory of growth.

Figure 8: implications of Polycentricity hypothesis