Section 4.11: Institutions

Hypothesis:

Notwithstanding recent progress, limited devolution to the West Midlands holds back our economy. Making the most of devolution—and effectively delivering a regional economic strategy of the kind proposed in our theory of growth—will require stronger horizontal and vertical links between public institutions and regional partners.

While progress is being made to devolve more powers and autonomy to the West Midlands and other English regions, further policy and fiscal devolution should be a key part of any West Midlands—and national—growth strategy. Understanding the impact of institutions on growth in the West Midlands can be more challenge than the other sub-systems for two main reasons. Firstly, institutions have indirect effects on economic performance: they influence the design and implementation of policy, rather than impact growth directly in the way skills, innovation and business support and housing do. Secondly, finding appropriate international comparisons to shed light on the impact of institutions on economic growth is difficult because local, regional and national contexts and histories vary significantly between countries. However, we think there is strong, albeit circumstantial evidence that the centralisation of power in the UK is an important structural factor in explaining the West Midlands’ economic challenges.

The UK is both unusually centralised and unusually spatially unequal. Local authorities in the UK rely on central government for over 60% of their funding and only raises 19% of its revenue through local taxes – much below the OECD average of 37%. For Combined Authorities – and the WMCA is not exception – almost all of its funding comes from central government grants. Across the UK as a whole only 6p in every £1 is retained by local government, the majority of that by local authorities in the form of Council Tax. A large share of local government’s spending in the UK is directed from the centre through statutory responsibilities and conditional grant funding. Legislative and executive power are retained overwhelmingly in Whitehall and the absence of a written constitution means that local government is constantly vulnerable to interference from central government. Alongside this internationally extreme centralisation of power is equally extreme regional inequality. As mentioned in the introduction, the gap between the most and least productive regions in the UK is as wide as the entire Eurozone. Additionally, across 28 broader economic measures of inequality, the UK was consistently one of the worst performers among OECD countries.

Historical data from OECD countries indicates that decentralised sub-central governance systems are largely conducive to stronger and more balanced interregional growth and development processes over the long-run. Case studies can help illustrate the potential impact of devolution on growth. For example, in 1990, Germany was 7.4% less productive than the UK, had a GDP per capita that was 8.0% lower than UK and was far more regionally unequal that the UK having reunified East and West Germany. Since then, Germany has invested an average of €70 billion per year – much of it granted freely to regional government under equalisation payments – on boosting regional equality. By 2017, Germany’s GDP per capita was 13.2% larger than the UK’s and it had higher regional equality; meaning that Germany growth over the 27 years outperformed the UK’s by nearly 21%.

We can also compare Scotland to the West Midlands. In 1999 – when the Scottish Parliament met for the first time – Scotland had a similar GVA per capita of £13,996, the West Midlands had a GVA per capita of £14,027 and the West Midlands region had a GVA per capita of £13,788.

Since then, GVA per capita growth in Scotland has significantly outperformed the West Midlands – as well as all areas in the country except London and the South East – and so is now approximately 18% higher than the West Midlands and 14% higher than in the wider West Midlands region.

Lastly, the history of growing spatial inequality and government centralisation seem to align in the UK. From the 1980s, HMG reformed and reduced the policy autonomy of local government and adopted an economic model that centred London as the motor of the nation’s economy that would attract and diffuse technology across the rest of the country. Over this time period, the amount of funding dedicated to regional interventions halved as a percentage of the UK’s GDP. Following these policy changes, regional inequality began to grow substantially from the early 1990s – approximately trebling on the Theil index between 1990 and 2010 while regions in the majority of other European countries were becoming more equal.

None of these pieces of evidence are strong enough on their own terms to lead to the conclusion that the centralisation of power in the UK is the primary driver behind the productivity inequalities holding back the country and the West Midlands. Our theory of growth has proposed a wide range of factors that explain why the West Midlands is not at its full economic potential. However, taken together we believe they make a compelling case that the centralisation of power in the UK is a fundamental economic constraint that helps to explain regional economic disparities in the UK and the West Midlands’ economic underperformance.

Further devolution to the region and local areas is, at a minimum, the ‘glue’ that holds together a locally-led economic strategy and will help to generate better economic outcomes. The Institute for Government, for example, has set out the specific mechanisms through which devolution can drive growth, by enabling policy interventions to be more closely tailored to local conditions; to be ‘joined up’ across different policy areas to amplify their collective impact; to be adapted in response to what works locally; by enabling greater policy experimentation and innovation; and by crowding in the resources of regional partners beyond the public sector. Furthermore, Professor Phillp McCann has articulated the role that sub-national institutions play in building investor confidence in the process of regional transformation, as a driver of economic development.

There has been some promising progress on devolution and decentralisation. The West Midlands has received its first Integrated Settlement, a £389 million funding package combining 21 funding streams from 7 different government departments, effective from 1 April 2025. The Integrated Settlement aims to bring improvements in the funding approach for the West Midlands. It will: eliminate competitive bidding processes; provide more local flexibility in policy design to realise mutually agreed outcomes; introduce longer-term funding visibility (two-year allocations from 2026); establish a “devolution by default” principle’; move away from fragmented, competitive funding models towards a more strategic, predictable approach going forward. However, there are still problems with this approach, including funding being tied to departmental remits, and improvements in funding efficiency not being a technical fix for the financial challenges facing local councils.

Despite recent progress and the fact we are heading in the right direction, there is potential for further devolution to the West Midlands. For example, only around 10% of skills and training funding that flows through the West Midlands is devolved to the WMCA. A third of publicly- funded business advisors are employed by public agencies other than the WMCA and local authorities. Whereas £761 million in public funding for translational R&D flowed through the WMCA last year, the proportion under devolved control was, as part of the Innovation Accelerator programme, a fraction of that at £11 million.

Making the most of devolution—and effectively delivering a regional economic strategy of the kind proposed in our theory of growth—will require greater local government capacity and capabilities in the West Midlands and denser horizontal networks with regional partners.

Devolution enables the West Midlands to lead its own economic transformation, but does not guarantee it. At the regional-level, the WMCA and its partners will need to strengthen their policy design and implementation capacities and capabilities. Internationally, evidence shows that strong local and regional government institutions that are integrated and have strong horizontal linkages with policy partners across places is associated with better economic outcomes. There are three key advantages to strengthen the horizontal links between the region’s institutions, outline below.

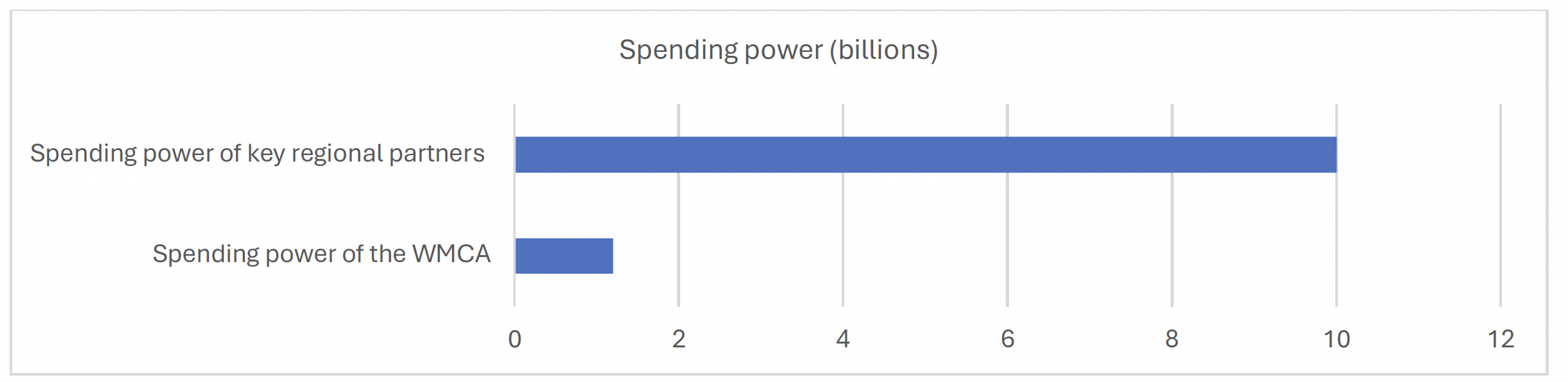

Firstly, to enable the West Midlands to leverage a larger amount of spending power to drive its economic transformation. There are many public and private sector organisations across the region that have a shared interest in driving growth and/or addressing the wider underlying challenges that hold it back discussed in this paper. To illustrate, Figure 35 below shows the annual spending power of key partner organisations across the West Midlands, illustrating that while the WMCA’s spending power is £1.2 billion per year, the total spending power of key regional partners is over eight times larger at around £10 billion per annum. This is a very cautious underestimate of the region’s collective spending power and excludes, for example, the West Midlands Pension Fund, which manages over £20 billion in assets.

Figure 36: Spending Power in the West Midlands19.

Secondly, to enable us to better understand regional challenges and opportunities. There is a real diversity of partners working in different policy areas and places across the region. We believe that this diversity of perspectives creates a range of expertise and ideas about how we could improve outcomes in the region. If we had greater capacity to align investments in the region and could draw from a wide range of knowledge, we think we would be able to improve our collective capabilities to address shared problems. Progress is being made towards this end in the West Midlands. In 2024, the region commenced an Economic Development Functions Review to look at how it can deliver activity in the most efficient, coherent and impactful way.

Third, to enable the region to be more innovative with its policy making and approach to delivery. We could work with our partners to test out and learn from experimental interventions that could be scaled or adapted across the region. Combined with a greater alignment of resources and sharing of knowledge to generate ideas, we think this experimentation would have an even greater potential to address some of the most challenging and sticky policy issues we face.

Connection with other sub-systems

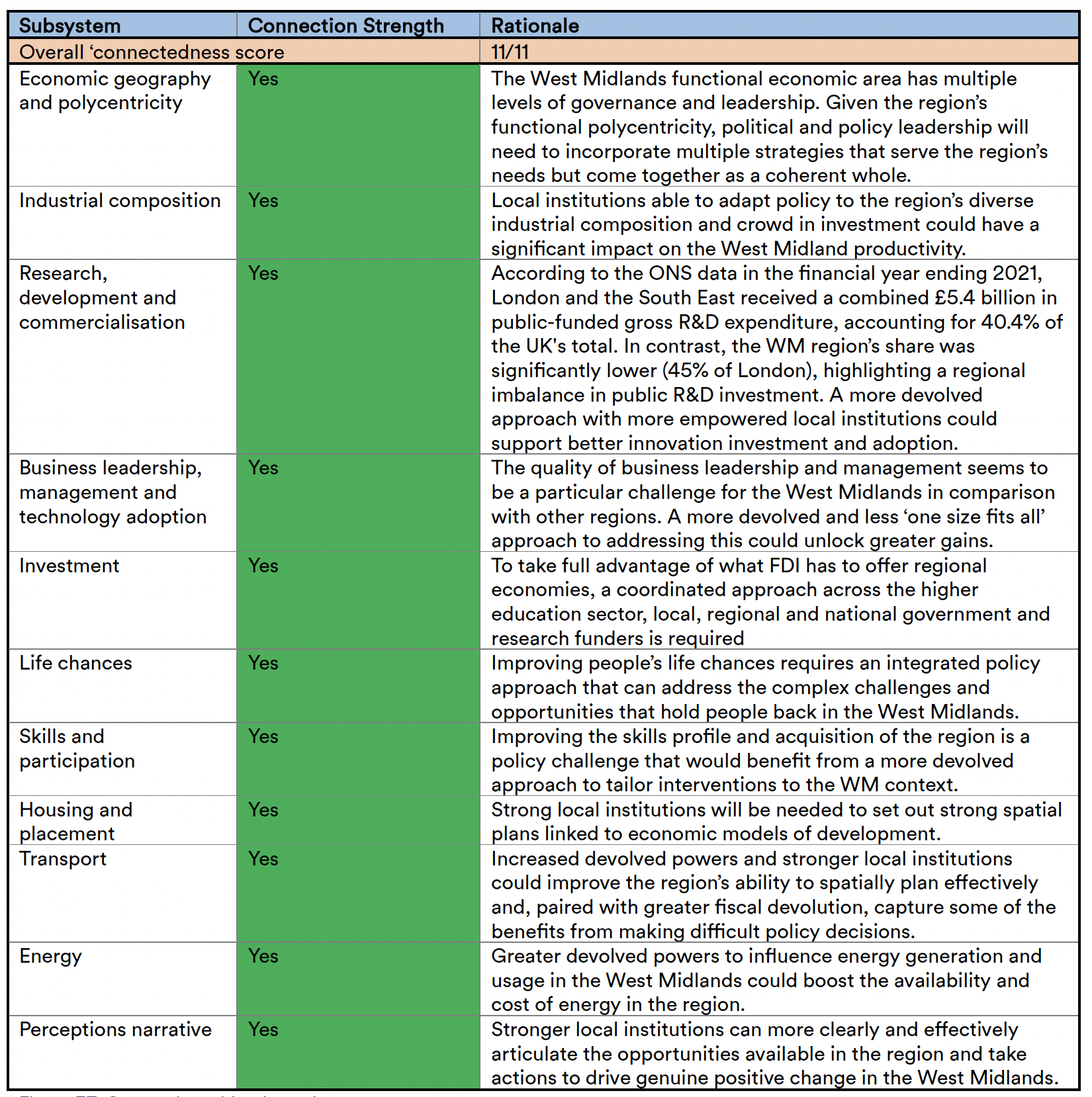

Figure 37: Connection with other sub-systems.