Section 4.2: Industrial Composition

Hypothesis:

The industrial composition of the West Midlands economy is a source of strength rather than a weakness.

Regional productivity differences result more from differences in firm-level productivity within sectors, rather than overall sectoral balance. A major study by CityREDI in 2023 found that the industrial structure in the West Midlands has a slight positive impact on regional productivity, but is not enough to offset low average business (firm-level) productivity. In other words, our industrial composition is not really a particular strength or weakness, but low firm-level productivity (lower by 11%) reflects that West Midlands businesses have a higher proportion of activity at lower points in value chains which often means operating with lower margins, management autonomy and investment.

There are a variety of reasons for this, including regional price differentials particularly in non- tradeable good and services. Sectoral data is also not ‘quality adjusted’—i.e., it does not account for different types of work within the same sector classifications like an international law firm in London has different specialisations to law firms undertaking local activity, which reflects occupational/skill composition and specialisation. Firm-level productivity differences can also be driven by a myriad of both internal (age, size, company structure/foreign ownership) and external (cluster agglomeration, market size) factors.

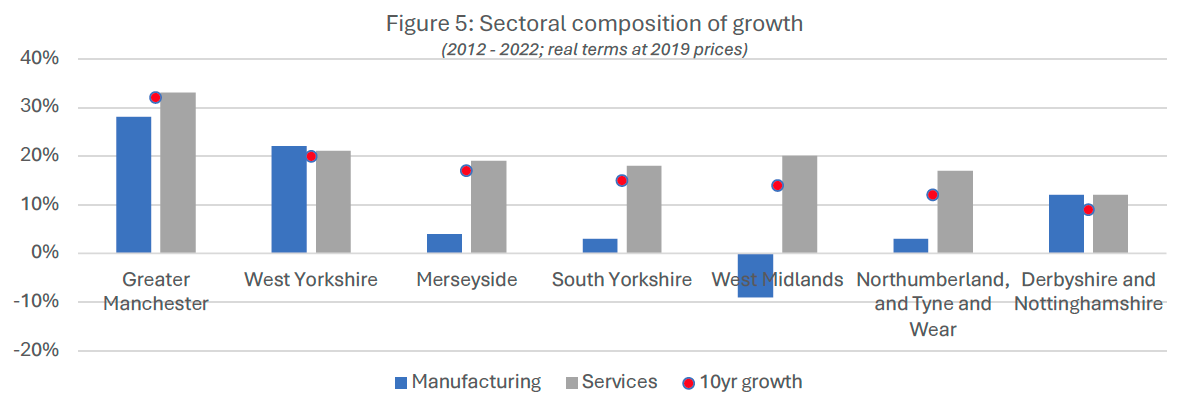

Across the economy overall, the WMCA area economic output has in the last 10 years grown at a similar rate to South Yorkshire’s and the North East’s, and slower than Greater Manchester’s and West Yorkshire’s. More rapid population growth in the West Midlands has meant output per head has been less strong. Within this, there are important sector trends: service sector growth in the West Midlands has been solid, although there have been particular challenges in manufacturing which makes up 11% of regional output but plays a vital role in our traded economy and wealth creation.

Figure 9: Sectoral composition of growth31

On services, the largest single cluster is business and professional services—producing 32% of regional output and 20% of jobs. Previous studies have emphasised that this sector is also important for other sectors in the region, including the broad digital sector. High-knowledge digital and professional service competencies are agile, often labour-intensive and mobile. It is positive therefore that the West Midlands position as the strongest region for FDI outside London is spearheaded by the software and IT services sectors, contributing 38 inward investment projects in 2023—the highest since 2017 and more than transportation and machinery manufacturing.

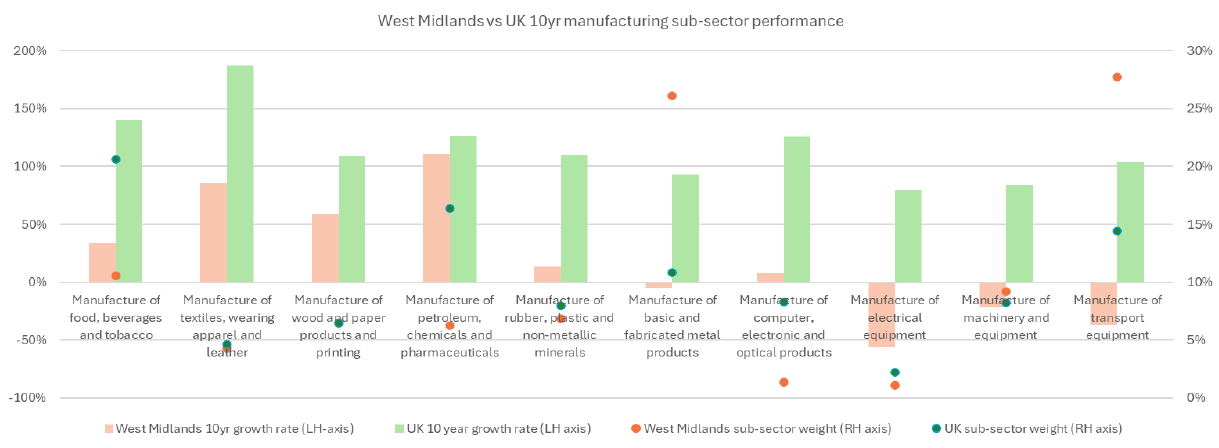

The last decade also sees the West Midlands as the only major city region economy to see a real terms decline in manufacturing output. Although compounded by our extreme focus on particular products and subsectors, the region’s output growth did not outstrip the UK on any manufacturing sub-sector.

- The manufacturing subsector that grew the strongest (petrochemicals, chemicals and pharmaceuticals) is a relatively small part of the region’s manufacturing base.

- The two sub-sectors where the West Midlands is very heavily-weighted (manufacture of basic metals & fabricated metal products and manufacture of transport equipment, including cars) saw some of the steepest reductions in real-terms output. We know, for example, that Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) was the second-biggest car producer in the UK in 2024, but its volumes have more than halved since 2016—when 544,401 cars were produced in its UK plants—as the JLR Reimagine strategy prioritises electrification, luxury and profitability over volume, with implications for regional output.

Figure 10: West Midlands vs UK 10 yr manufacturing sub-sector performance

The multiple shocks of the Covid pandemic, disruption to international trade, energy crisis and emphasis on defence and national security have recalibrated how major manufacturing supply chains balance cost optimisation with resilience, sustainability and collaboration with customers and suppliers. Within this shifting commercial context of managing uncertainty and risk, Government has initiated a more activist industrial strategy, with the Invest 2035 Green Paper articulating a 10-year plan to deliver the certainty and stability businesses need to invest in the high growth sectors that will drive our growth mission. Its focus is boosting productivity, job quantity, job quality and overcoming barriers to eight growth sectors. The West Midlands has been recognised as having strengths in each of the eight priority sectors identified in the national Industrial Strategy. As a result, the WMCA and the region’s cluster leadership groups have been working with the Government to shape Sector Plans to be published in June 2025, instilling confidence and direction in the UK’s growth sectors.

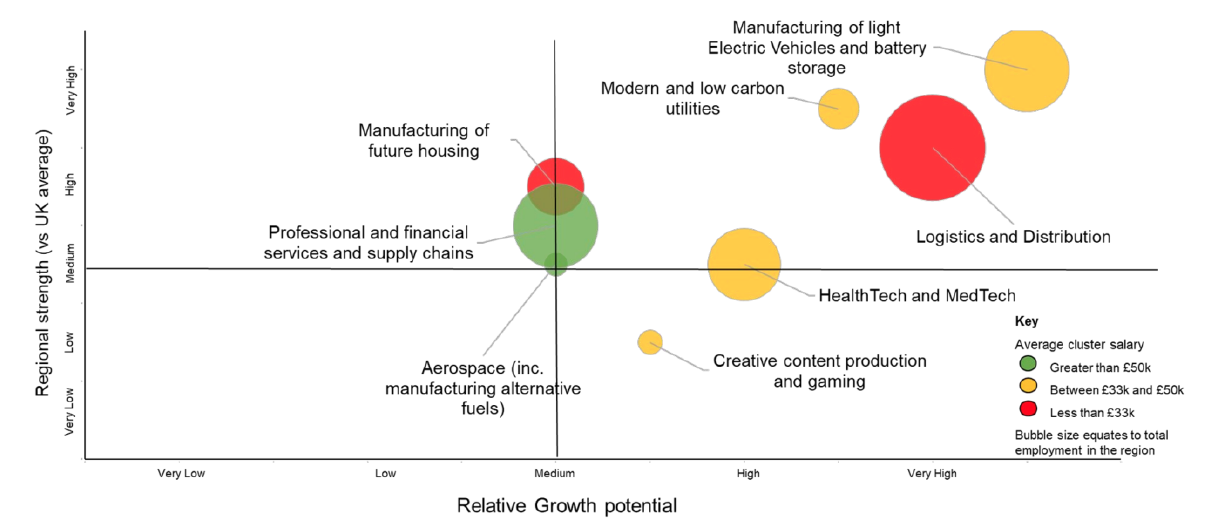

Part of the reason why the West Midlands is prominent in each Sector Plan is because we have a clear rationale about the different reasons why each sector is important to our future economy, because different parts of the economy have different prospects on productivity, jobs and output growth.

Figure 11: Most significant growth sectors and clusters, and their growth potential in the region.

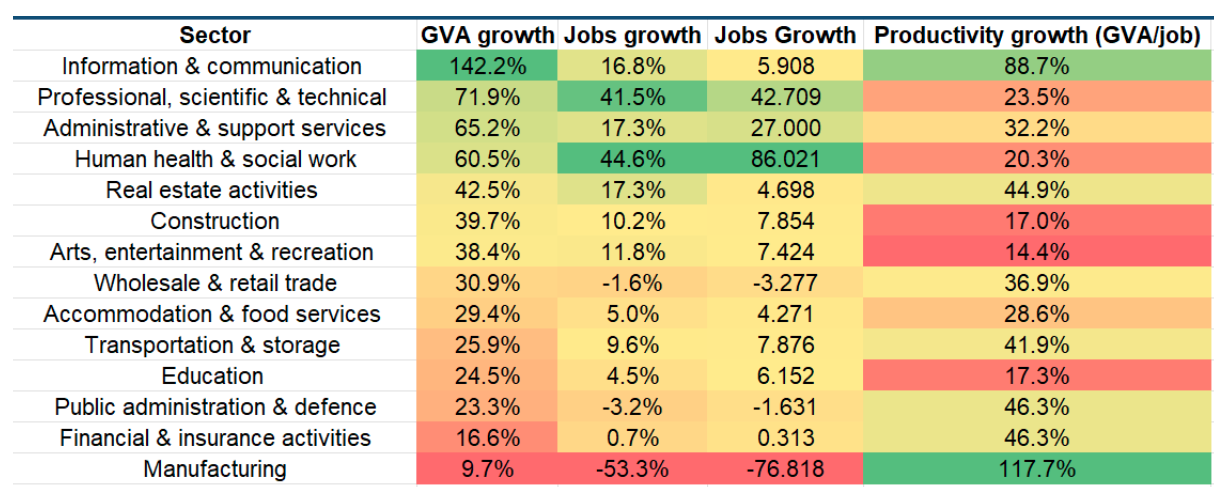

Our industrial composition as it is today will not look like how it does in the future. Using the Oxford Economics baseline forecast for 2019 – 2050 (Figure 12, below), we project that:

- The region’s four most tradable sectors—digital; professional services like architecture, legal and management consultancy; financial services; and manufacturing—occupy the top two and bottom two slots on forecasted output growth. However, they tell very different stories about forecast trends on jobs and productivity.

- Other aspects of the economy—construction; retail; health; education; logistics; and public services—equally have very different profiles on job creation and productivity.

Figure 12: Oxford Economics forecast of sectoral change in the West Midlands economy between 2019-2050, with the colours indicating the relative degree of change (green highest increase; red lowest decrease).

Our central proposition is that the West Midlands should not seek to reach a different sector balance, but to help firms with lower levels of productivity relative to the sector move up the value chain into higher productivity activities. The region’s growth plan combines the agglomeration effects of supporting clusters of strength to drive above-forecast growth but addressing specific cluster barriers in the following subsystems, along with a focus on firm-level development. The business leadership, management and technology adoption subsystem helps business leaders navigate their path to higher value, more productive work to address the West Midlands challenge that the inter-regional productivity gap stems from firm-level productivity within sectors, rather than overall sectoral balance.

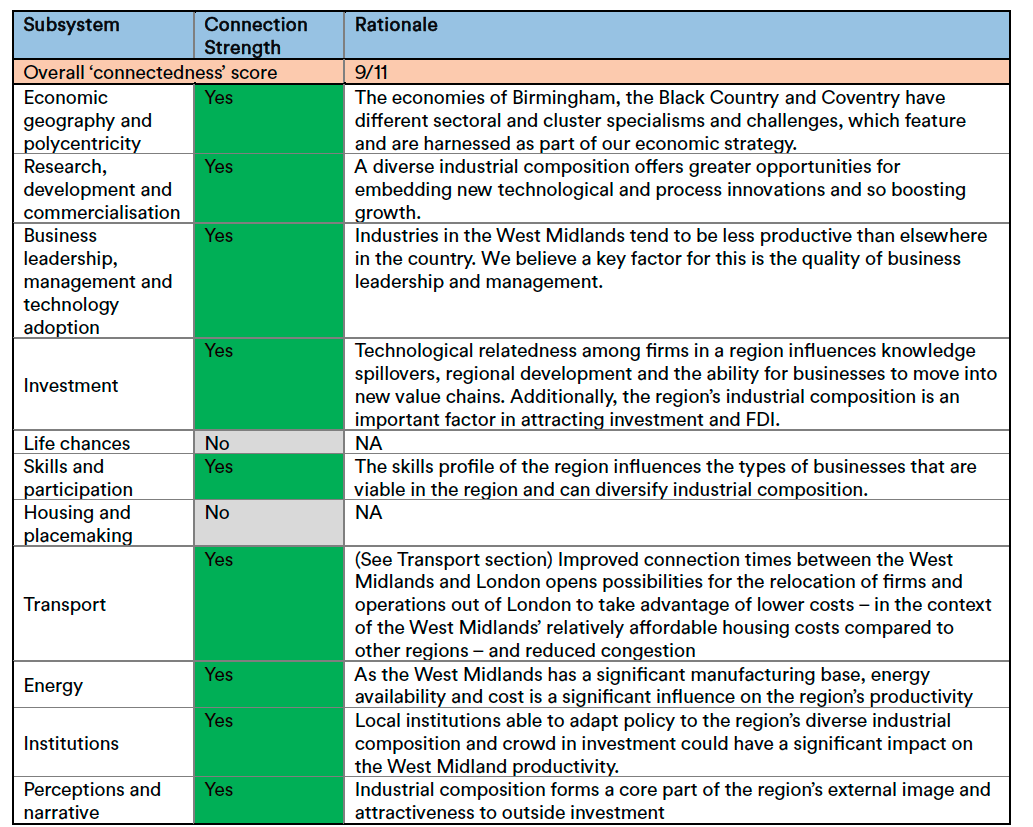

Connections with other sub-systems

Our industrial composition hypothesis has implications for several other sections of our theory of growth.

Figure 132: Industrial hypothesis implications