Section 4.6: Life Chances

Hypothesis:

Giving every child and young person better starts in life is the most important action we can take to enable them to live longer, happier, more purposeful, productive and fulfilling lives. For working age residents of the West Midlands, far too many reduce their hours or leave the labour market entirely to undertake caring responsibilities, reducing their earnings potential, which affects women in particular. Alongside this, there are well-evidenced racial inequalities in the labour market and economy that affect a significant number of West Midlands residents.

The population of the West Midlands is growing, young and diverse—but also faces a broad range of challenges linked to high levels of deprivation. The West Midlands State of the Region report provides a comprehensive overview of the region’s population profile, summarised as follows.

- The WMCA is the second largest city region by population in the UK. Over the next two decades, its population is expected to grow by 380,000, the second largest relative share of growth of any other city region. This compares to the situation in some other countries which are forecast to see a declining population over time.

- The WMCA is also the second youngest city region of the UK, bar Greater London, and is home to one of Europe’s youngest and most ethnically diverse cities, Birmingham. In Birmingham, some 28% of the population is under the age of 20, and 36% is under the age of 25. Its youthful population is expected to continue to grow over the next 10-15 years. However longer-term population projections suggest that the over 65s population will also be fast growing across all seven districts of the West Midlands metropolitan local authority areas.

- The WMCA is a highly ethnically diverse region, with 44% of our residents identifying as being from an ethnic minority background. White British are the largest ethnic group at 56%, accounting for 1.6m of our 2.9m residents. Around 20% of our residents have a Pakistani, Indian or Bangladeshi background, and an aggregate of 10% have a Black heritage. Only Greater London is more ethnically diverse than the West Midlands.

- Faith plays a significant role in the lives of our residents. 66% of WMCA residents practice a faith, the highest of any combined authority area. The makeup of our faith communities is also very diverse compared to the national picture, with strong representation of Muslim (17.2% in the West Midlands vs 6.5% nationally), Sikh (5.1% vs 0.9%) and Hindu (2.3% vs 1.7%) followers.

On account of the facts above—our large population, young demography, ethnic diversity—the West Midlands could be said to have a demographic dividend within reach. However, the evidence shows that there are serious barriers holding back our residents from being able to fully participate in the economy, which also hold back our economy.

Early years and youth employment. Children in the wider West Midlands region are more likely to die in childhood than in overall for England. While there are some bright spots in some parts of the region when it comes to children’s school readiness, the overall picture of early years development in all parts of the region—with the exception of Solihull—is a challenging one relative to the national average. The WMCA has the highest levels of poverty nationally, with child poverty (43%) having long-lasting impacts on life chances. Almost half of children in Birmingham (48%), Sandwell (47%), Walsall and Wolverhampton (46%) were in families living in poverty in 2022-2023. By the age of 16, children in the WMCA area across all ethnic groups achieve lower Progress 8 scores, a measure of educational progress, than the England average.

These cumulative factors set back our young people back and create barriers to work. Our youth claimant rate (8.8%) is higher than the UK average (5.0%) and is rising faster. We see particularly high rates in Wolverhampton (10.7%), Birmingham (9.9%) and Walsall (9.4%) where around one in ten young people are unemployed. The number of youth claimants has increased by 9.6% in the last year and by 30.1% since March 2020 pre-pandemic. Between 2012 and 2021, the proportion of young people not in employment and training reporting a mental health issue tripled from 7.7% to 21.3% nationally. NEET prevention teams across the region are also increasingly citing mental health as a major barrier to young people’s engagement in education and work.

Given the youthfulness of the West Midlands’ demography, our theory of growth recognises the need to ensure children across the region are well-prepared as they start school and remove the barriers between young people and employment.

Economic inactivity, caring responsibilities and inequalities. 26.1% of our working age residents, or nearly half a million (487,600) people, are classed as being economically inactive. This is the highest relative share of all other combined authority areas. Over a quarter of this figure, or just under 122,000 people, are economically inactive because of their caring responsibilities. Economic inactivity due to caring responsibilities in the West Midlands is substantially higher than the second-highest combined authority area (Greater Manchester, where 19.2% are economically inactive for this reasons). This role remains predominantly gendered, which largely explains the gender disparity in economic participation and is one of the key reasons why women in the WMCA area earn 11% less than men, despite having similar levels of highest qualification achieved, and face a 7.4% employment gap.

To put this into perspective, if, hypothetically, the number of people who are economically inactive but caring for people entered employment (122,000), the West Midlands would close its employment gap with the national average. While this is a hypothetical illustration, the impacts of closing the gap even by a share of this figure, as reported by parents themselves, would be significant. Analysis by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation shows two out of three parents would work more if there was more funded childcare provision. Similarly, the Rose Review found that £250 billion of new value could be added to the UK economy if women started and scaled new businesses at the same rate as men. While 1 in 3 entrepreneurs nationwide were women, male-led SME’s are 5 times more likely to scale their businesses to over £1million; and only 1% venture capital funding went to businesses founded by all-female teams.

Because of the scale of this constraint, our theory of growth recognises the need to support our residents with caring responsibilities to increase economic activity.

Ethnicity, labour market inequality and underemployment. There are clear racialised inequalities in jobs and skills outcomes for WMCA residents: on aggregate, people from racialised communities are more likely to be economically inactive and are around twice as likely to be unemployed than White British people. The employment gap for people from racialised communities is 5.9% compared to White British people, and the race pay gap in the West Midlands is around 7.5%.

These inequalities point to discrimination in the labour market. Overall, Black, Asian and other racialised or ethnic minority groups perform well in education and are characterised by relatively high rates of participation in post-compulsory education, but success in education does not translate to success in employment—both in terms of both employment rates and types of jobs. Using a definition of underemployment as a lower level of actual employment for a particular ethnic group than predicted employment based on the employment rate by qualification and age across the population, it is estimated that in 2019 employment for people from minority ethnic groups in the WMCA area was 38,300 (or 9%) lower than it would have been if employment rates by qualification matched the average in 2022, a reduction from 54,500 (or 14%) lower in 2019. In both years, estimated underemployment was greater for women than for men.

Evidence indicates that, on average, individuals from ethnic minority groups make more applications to get a job than their white counterparts. In addition, the duration of unemployment tends to be longer for individuals from ethnic minority groups, and this is associated with wage penalties and cumulative disadvantage. There are a range of barriers that at least some racialised communities experience at different stages of their lives from early life career aspirations, through education and training, transitions into work and in-work progression. This research resonates with qualitative insights from Youth Futures Foundation and Youth Employment UK, which show young people are concerned about facing race discrimination in the workplace.

As well as constraining labour market outcomes, racial inequalities also constrain entrepreneurship and business growth. Leading studies from the Centre for Research in Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship at Aston University has found that people from ethnic minority communities are two times more likely to start a business than the population generally.

However, just 43% of ethnic minority-led businesses go on beyond the 42-month mark (at which point a business usually becomes income generating), while for white-owned companies that figure is 67%. CREME contend that removing the barriers to success, such as difficulties in accessing finance, that ethnic minority businesses face could enable them to quadruple their national contribution to GVA, from £25 billion to £100 billion annually. The WMCA is seeking to close the entrepreneurship gap and has launched an action learning project to connect ethnic minority-led businesses to available growth support, through Business Growth West Midlands, the Race Equalities Taskforce and 5 community led hubs (2024).

Our theory of growth recognises racialised barriers to prosperity as a constraint on the region’s economy—one that it affects up to 45% of our residents.

Health and its economic determinants. People in the WMCA area die earlier than the England average. Aligning with national trends, life expectancy in the WMCA is declining and the gap between the WMCA life expectancy and the England average is widening. The WMCA area performs less favourably than England on several measures, including: higher mortality rates for cancer, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory diseases; lower rates of physical exercise; higher rates of obesity, and worsening conditions contributing to the fastest growing rate of child poverty in England (Towers et al., 2024). The rise in work-limiting health problems and long-term sickness or disability as reasons for economic inactivity in the West Midlands have risen faster than in the UK as a whole (Green and Houston, 2023). Long-term health problems or disability that limit the type or amount of work that can be done rose in the West Midlands by more than 1- in-50 of the population aged 16-64 years (from 10.6% to 12.8%) during the three years 2019-22, around double the rate of increase for the UK as a whole (Green and Houston, 2023). More recent evidence shows a sharp increase since the COVID-19 pandemic in the prevalence of health problems among the population of working-age (16-64 years) and that this has contributed to rises in economic inactivity (Houston et al., 2023; Health Foundation, 2024).

26.7% of the WMCA population is disabled according to the Family Resource Survey 2022/23. This represents 780,000 of our residents and is a higher proportion that the England average (24%). Evidence shows that disabled people score worse on all wellbeing indicators than their non-disabled counterparts, and find it more difficult to travel and secure good qualifications, housing and employment. Disabled entrepreneurs currently account for approximately 25% of the nation's 5.5 million small businesses, but only 8.6% of total small business turnover. Four fifths feel they have unequal access to opportunities and resources. Estimates suggest that improving opportunity for disabled founders could unlock an additional £230 billion for the UK economy. Spearheaded by Small Business Britain, the Lilac Review will identify barriers facing disabled entrepreneurs and how these can be addressed.

Our theory of growth recognises the burden of ill-health on our economic performance. The overarching focus of our economic strategy is to address the economic determinants that drive ill-health in the first instance.

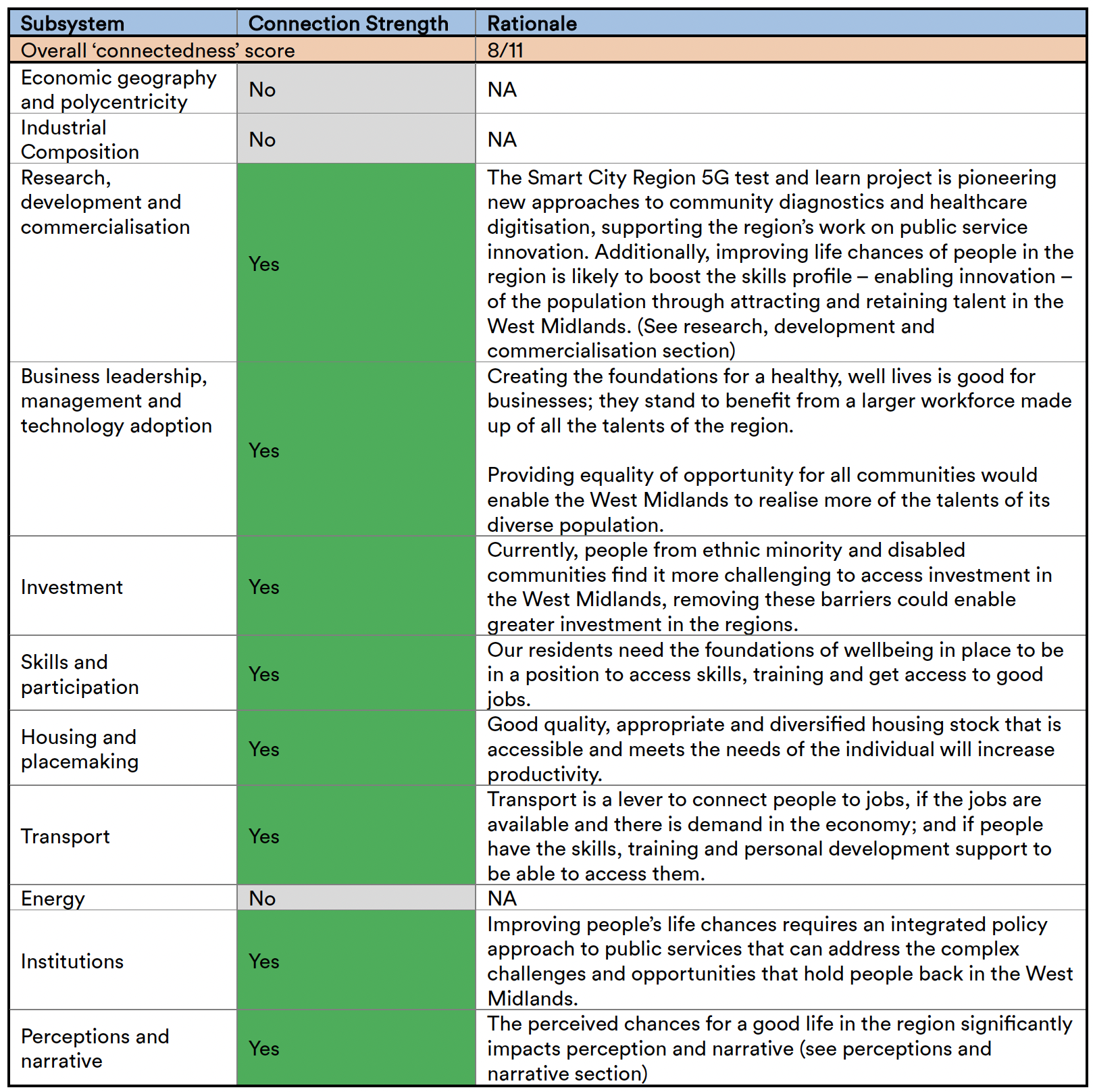

Connection with other sub-systems

Figure 25: connection with other subsystems.