Section 4.8: Housing and Placemaking

Hypothesis:

The West Midlands' housing system is constraining regional productivity through stifling agglomeration benefits, displacing investment, reducing household resilience and increasing deprivation. Addressing these challenges will require the region to significantly increase house building across different tenure types, densify housing in urban centres and around the region's transport hubs, helping to create the conditions for vibrant high streets.

There is an undersupply of the right mix of housing in the West Midlands that leads to an affordability challenge. In the West Midlands, there is strong evidence of the undersupply of the appropriate types of housing in the right places, leading to a significant affordability challenge.

Housing is the largest single expense for households in the West Midlands: private renters spend more of their income on it the West Midlands than they do anywhere in England except the South East, London and South West. The median price of a house in the WMCA area is 6.61 times the median workplace earning – above the maximum ratio of 5 the ONS defines as affordable and having increased significantly from the 4.77 ratio in 2013. Lastly, there are more than 64,000 households on social housing wait lists already, with 5,600 living in temporary accommodation.

The Resolution Foundation estimates an additional 116,000 homes will be required over the next 15 years in the ‘Birmingham Urban Area’—a level of housebuilding that would require a doubling the recent housebuilding rate alongside addressing skills shortages in the regional construction industry to support this level of activity, but is in line with our latest target of 244,000 homes in the West Midlands over 20 years. Not all of the homes the region needs to build will be funded by the public sector, but where the WMCA role has a role as a gap funder for sites which would not be brought forward without public sector intervention its focus is on utilising derelict or underused brownfield sites to unlock new homes. For example, the WMCA is helping to transform the West Works site at Longbridge and working closely with Sandwell Council on Friar Park Urban Village, a new residential community and is the largest brownfield development for housing in the West Midlands.

Although the supply and affordability of housing is a challenge for the region, some groups are particularly effected. For example, temporary accommodation: two thirds of the lead applicants were women, more than half were single mothers, and people from Black African backgrounds as well as those households with a disabled family m/8/8/ember were overrepresented. Interviewees living in temporary accommodation identified the private rented sector as being a key issue, and raised concerns around poor quality and unaffordable housing, as well as debt and unstable employment.

The undersupply of housing reduces productivity by: (1) redirecting investment away from more productive activities; (2) increasing deprivation and creating cost pressures on public services; and (3) reducing household resilience.

Redirecting investment away from more productive activities. Investment into housing, land and real estate generates few positive technology spillovers and innovation which can drive productivity and growth. Instead, it can displace investment that otherwise would have flowed to other more innovative sectors of the economy; damaging productivity growth over the long- term. This is particularly true in economies – like the UK – where the value of housing and land as an asset has outstripped growth in the rest of the economy and other assets. Across the country, 1 in 5 homes are now owned by private landlords.

The OECD has noted there is a significant and negative relationship between high house prices and productivity in a dataset covering 24 countries over almost 50 years. Although the effect in the UK was noted to be less strong, on average across all countries over the time period an increase of housing prices by 55 basis points corresponded to a 1% reduction in labour productivity growth. High house prices in city centres in particular may be inducing people to move away from urban areas – negatively impacting productivity by further shrinking the effective size of the labour market – as well as making it more difficult for city centres to support the vibrant culture that attracts people to them.

In the West Midlands, the prices of housing have been rising rapidly relative to wages and the regional economy’s size. If this trend continues, it creates the risk of dampening future investment demand into productive economic assets and overall future growth.

Increasing deprivation and the cost of public services. Living in poor quality, cold and damp houses also increases incidences of health issues, reducing people’s ability to earn and further fuelling poverty, while growing up in poor housing conditions is strongly associated with diminution, lower future earnings and underutilisation of lifetime human capital. This ultimately leads to higher public spending pressures, by increasing the demand for social services and drawing funding away from other potential investments. The Centre for Economics and Business Research estimates that the annual direct savings to the exchequer from building one social housing unit is £6,222 per year through reductions to benefits, health care costs and increases in tax receipts alone. If the West Midlands were able to clear its social housing backlog then, we could expect this to free up almost £400 million of public spending in the region per year.

Reducing household resilience. Where housing costs are high relative to income, households are less able to withstand economic shocks. Economic shocks can lead to increases in inflation and/or interest rates, availability of credit, as well as changes in employment status. These factors reduce households’ disposable income and their ability to maintain or retain their housing. Where housing costs are lower relative to income, there is more flexibility in household income to manage these periods. Lower resilience to economic shocks as a consequence of relatively high housing costs is likely to be an issue in our region. The average net income once housing costs are deducted is lower across our region compared to the English average - £25,900 across the WMCA constituent authority area compared to £29,700 for England. Within this regional average, there are areas that are likely to be less resilient than others, for instance, MSOA 058 in Birmingham has an average net income once housing costs are deducted of £16,800 per annum, and MSOA 052 in Birmingham £16,300 per annum.

The houses we are building aren’t in the right places or dense enough, creating more car dependency and reducing the vitality of our high streets. Internationally, it is generally the case that the larger a city is, the greater the productivity of its workers. Economics literature and research explain this phenomenon through the concept of agglomeration: the positive productivity benefits urban locations gain from having large numbers of workers and businesses located nearby and therefore accessible to each other. However, somewhat uniquely, cities in the UK—particularly outside the South East of the country—do not seem to enjoy agglomeration benefits. That is to say, there is a very little relationship between productivity and size of cities. This constrains the ‘effective labour market size’ of the UK’s cities (the number of potential workers who can access job opportunities easily during peak travel hours) and so prevent the realisation of agglomeration benefits.

A major explanation for this small effective labour market size is low housing density. In the West Midlands, Birmingham’s urban core is only a third as dense as London for example. The Centre for Cities has also compared the density of Birmingham to Munich, a relatively economically successful German city; and finds that whereas 74% of Munich’s population can access the city centre within 30 minutes, only 34% of Birmingham’s population can despite the fact Birmingham has a larger transport network—indicating that the core difference is the density of housing. Evidence from the New Economics Foundation suggests homes are being built at an increasing rate outside of our urban centres and in rural areas, for a number of reasons.

Low housing density makes the maintenance and regeneration of vibrant high-streets in the region much more difficult. Besides the economic advantages of density—and the associated benefits this can bring to high-streets—increasing the population within a given area is associated with more successful local high-streets. Building more housing and more densely is a key ingredient to reviving and sustaining vibrant high-streets and to ensuring the new houses we are building offer desirable places for people to live that are well connected to other parts of the region and the landscape and cultural amenities it offers—our geographic diversity being one of our regional strengths.

In the context of the West Midlands’ polycentric structure, densifying housing and the placemaking activity it supports cannot be pursued in and around Birmingham alone. A more appropriate approach is to embrace the opportunities across the urban cores of our cities and boroughs plural, and ensure they are well-connected to each other. In the Resolution Foundation report, for example, they propose that 87,000 of the new 116,000 homes for the Birmingham Urban Area should be developed in the city centre while 29,000 should be developed outside this area but within 500m of a railway station less than 30 minutes from the city centre.

This strategy is commonplace in polycentric regions overseas, such as in Belgium, and would play to the strength of the region’s polycentricity. We are already seeing this strategy start to take route in the West Midlands, with proposals such as the City Centre West Development in Wolverhampton, City Centre South in Coventry, housing and regeneration efforts in Dudley around the Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Metro Corridor and Walsall’s Town Centre Masterplan, while the extension of the East Birmingham – Solihull Metro would link a population the size of Newcastle upon Tyne into Birmingham city centre. These example projects integrate, to different degrees, housing development, placemaking, the revisioning of the role of high streets and alignment with transport hubs.

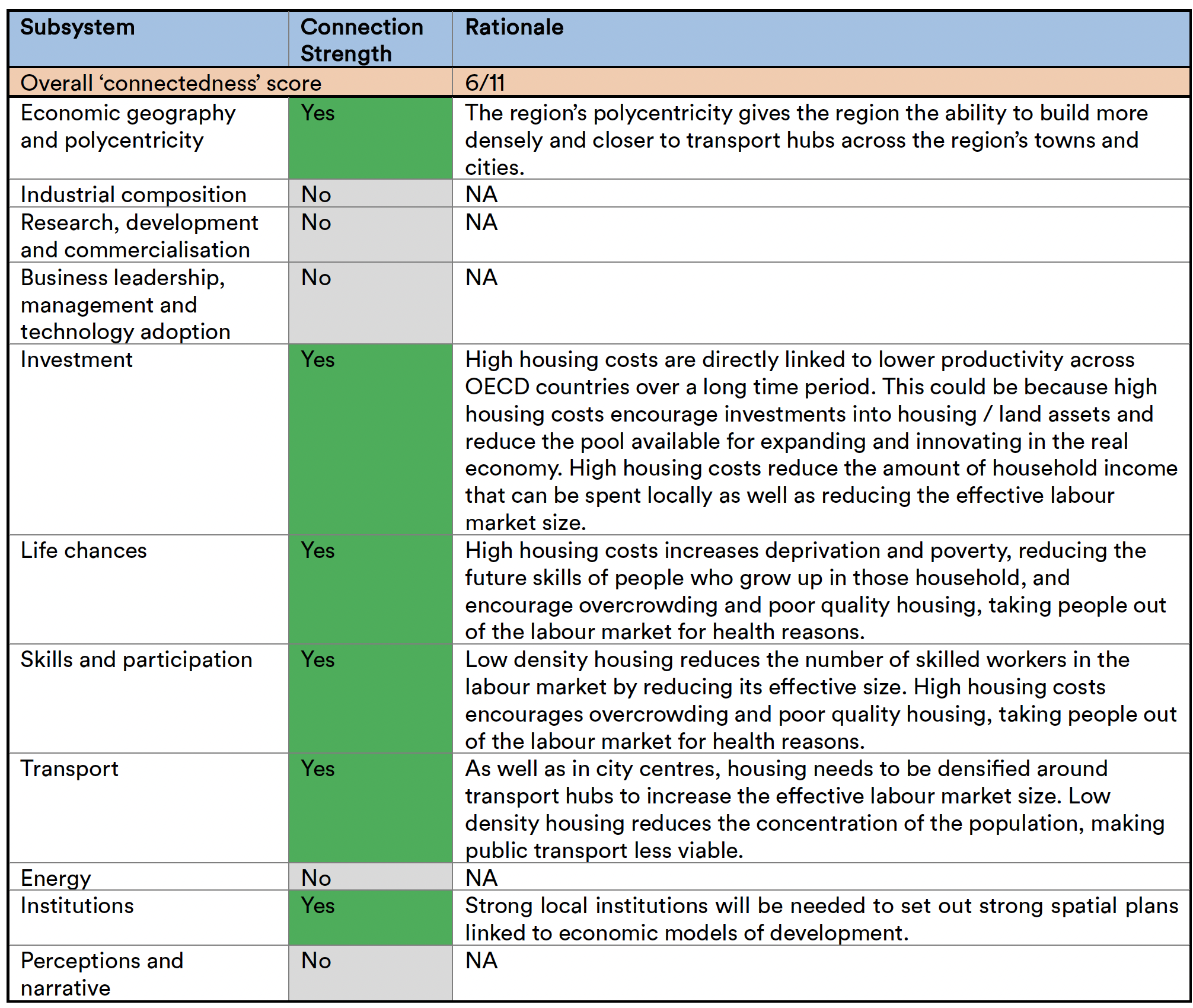

Connections with other sub-systems

Figure 30: Connection with other sub-systems.