Section 4.9: Transport

Hypothesis:

Because of our polycentricity, the West Midlands needs to better connect our boroughs to our cities and our cities to each other and improve public transport connectivity into Birmingham specifically, helping to reduce the region’s car dependency.

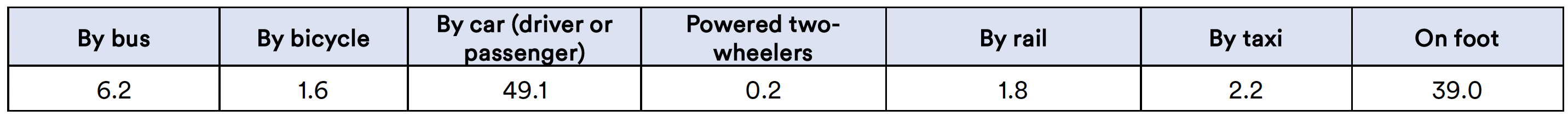

How do people move around our region? Mostly by car and on foot.

Figure 31: How do people move around our region (Source: TfWM Modal Share: April 2024 to March 2025 – Blended method).

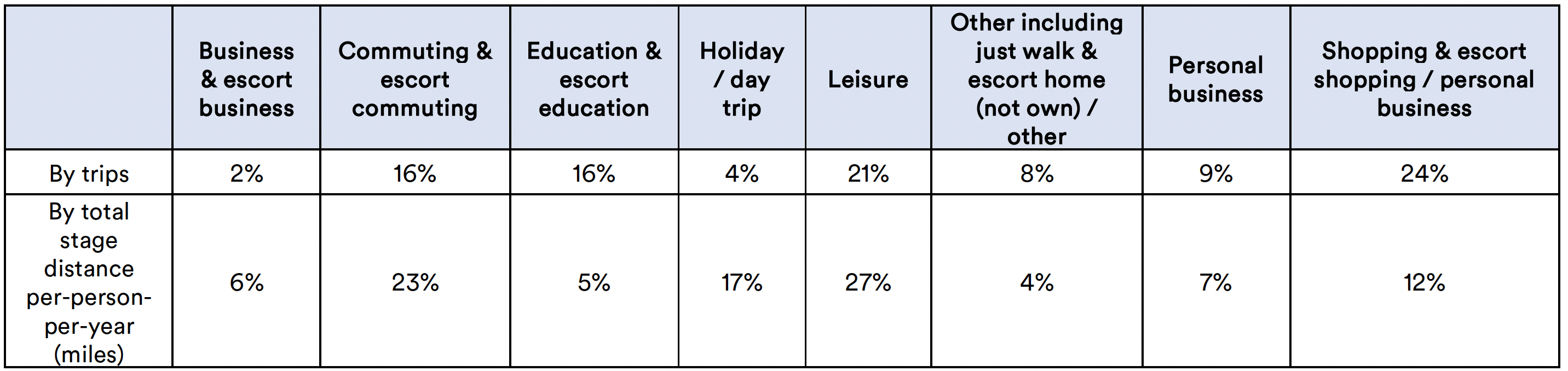

Why do people move around our region? Mostly for leisure and shopping, then for work.

Figure 32: Why do people move around our region (Source: National Travel Survey 3-year average 2019, 2022, 2023).

Transport shapes local economic growth by enhancing connectivity, reducing travel times, and fostering trade and labour mobility. Extensive research has demonstrated that investments in transport, whether in urban rail, high-speed rail (HSR), or road networks—can lead to significant economic transformations. However, transport investment on its own will not automatically lead to economic benefits. If misaligned with existing or potential travel demand and development opportunities, transport investment can simply create underused capacity in the transport system.

It is important to note that while transport is an economic growth lever, this isn’t its only function. It has social and environmental purposes, too. Most notably, up to 2,300 people die early due to long term exposure to air pollution every year in the West Midlands; while there were 57 fatalities on the West Midlands’ roads (2022) with a slight decrease of 49 (2024) and around 950 people suffer from serious, sometimes life-changing injuries each year. These are serious issues that demand attention. The role of this theory of growth is to look primarily at the primary economic functions of transport.

Overall, West Midlands’ residents are making fewer but longer journeys. But even today, transport is a constraint on our economy. This will only increase against the backdrop of projected population increase of 380,000 over the coming two decades. This is most acute with respect to Birmingham, home to the busiest train station outside of London and 42% of the WMCA area’s jobs, around 70,000 of which are held by WMCA residents from outside of Birmingham.

- Using TfWM data, between 2008 and 2018, over 200,000 fewer residents were able to access Birmingham city centre by bus within 45 minutes as a consequence of increased traffic creating congestion and increased levels of on-street parking (reducing capacity), and other factors.

- The National Infrastructure Commission projects that transport will constrain future growth in Birmingham more than any other UK city. Birmingham will see the most growth in city-centre jobs but has the lowest transport capacity hence the size of its capacity gap. The Commission argues the city should be a priority for mass transit investment.

- While rail represents only a small number of journeys (c1%), Birmingham’s rail network is, of all cities in England and Wales, the busiest during morning peak times and the second busiest during afternoons and evenings —reflecting the local, regional and national functions of the West Midlands’ transport system.

While the pressures on Birmingham’s transport connectivity are acute and need to be addressed, our polycentric economic geography requires a broader focus than just on Birmingham alone. As we saw in the polycentricity sub-system, transport is one of the key levers available to the West Midlands to more closely integrate our boroughs to our cities and our cities to each other and realise the advantages of our polycentric geography. The benefits of functional integration extend both ways: businesses that are looking for the particular characteristics that cities have to offer get access to an expanded workforce; and residents of our boroughs get access to jobs in cities that may not set up in boroughs. There is some evidence that places with higher commuting links into Birmingham have higher wages. Fiscally, this serves cities which benefit from the additional business rates generated by the additional economic activities they are enable to accommodate; and the boroughs in the form of a more stable Council Tax base by strengthening residents’ earning potential. Progress is being made towards better connecting our boroughs to our cities and cities to each other. However, as we saw in the polycentricity sub- system, the flows of people between our cities and our boroughs is too low.

Addressing the constraints on the public transport system requires a detailed understanding of the factors preventing residents from using it. In the West Midlands, the affordability of transport is a major issue—it is the biggest household cost after housing—and some residents are discouraged from using public transport by safety concerns. Just increasing the supply of ‘hard’ infrastructure without addressing these barriers is unlikely to shift users’ behaviours towards using public transport and alleviate congestion on the network.

In addition, increasing the supply of public transport is not the only lever to be pulled to alleviate pressure on the network. We need to reduce the demand for transport, too. 60% of trips of 1 – 2 miles in length are made by car, many of which could be made by other modes of transport like active travel: walking, wheeling, cycling or scooting. Building denser neighbourhoods where core services are easily accessible—known as 15-minute cities—would help to enable this, alongside making our streets safer.

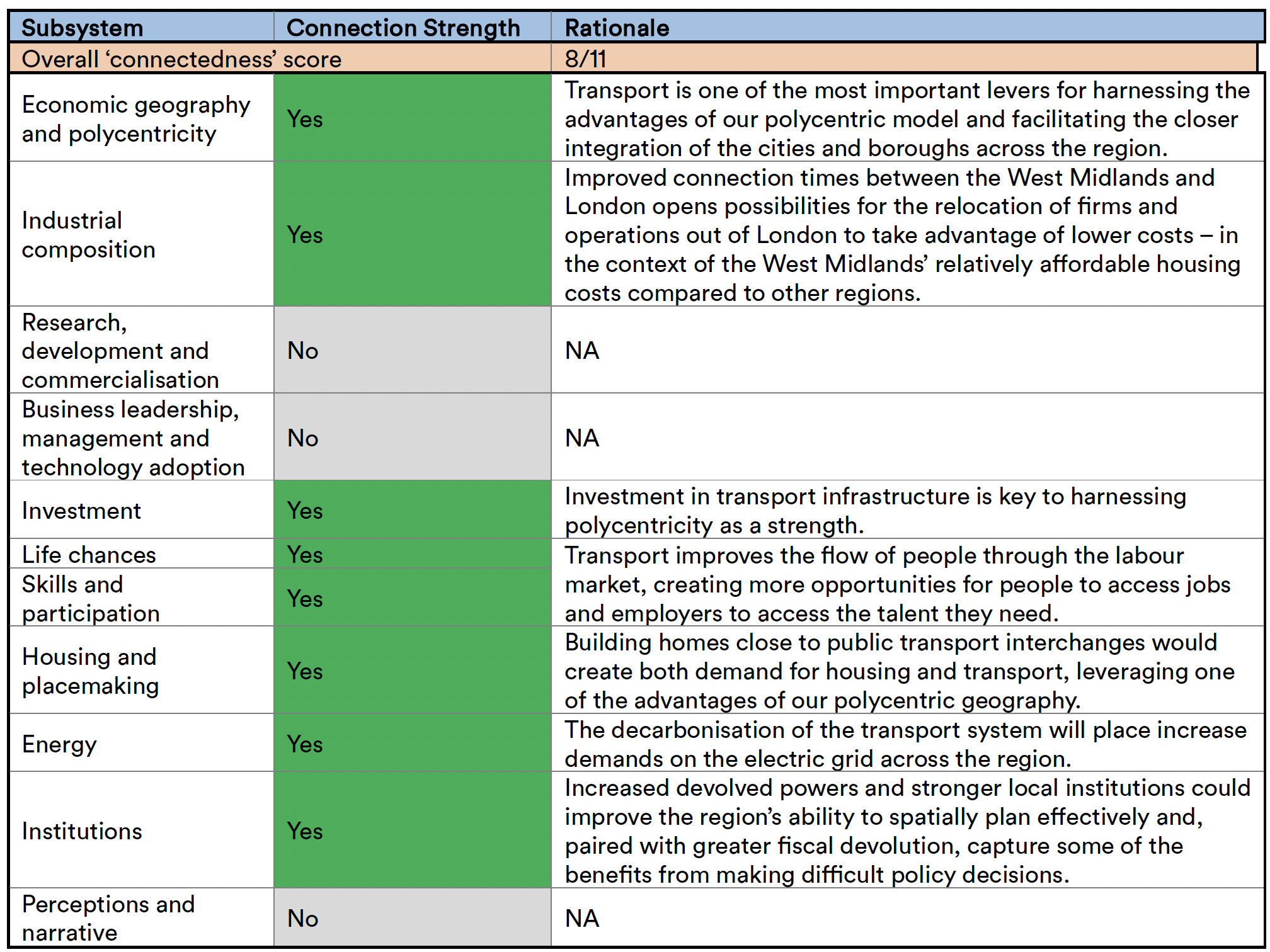

Connections with other sub-systems

Figure 33: connection with other subsystems.