Section 5: Conclusion—A Whole Systems View

The West Midlands’ theory of growth gives a holistic view of what the challenges and opportunities are to realising our vision of inclusive growth—higher living standards across all parts of the West Midlands. It acknowledges that to achieve economic transformation, we need to attend to the region’s key drivers of growth in parallel as part of a joined-up strategy, which local, regional and national partners have important roles in delivering. Developing our understanding of what needs to change has involved using West Midlands-specific evidence to identify and analyse 12 sub-systems that we believe interact to create the low-productivity, low- wage equilibrium that is at the core of why the region is not yet at its full potential. Against each of these sub-systems, the West Midlands’ theory of growth sets out hypotheses that capture the essence of what the key challenge and/or opportunity is, which will enable us to test our understanding through a programme of action learning.

While our theory of growth has sought to be holistic, it has also sought to prioritise—both in terms of which challenges and opportunities to focus on in the first place, and in distilling what the core essence of each is. The next stage of developing our theory of growth will involve engagement with our regional partners and further analysis to understand which priorities are the highest priorities, taking our analysis a step further to the next level. Below, we set out some of the factors that will be considered to help us prioritise our priorities.

Some sub-systems are more central to economic transformation than others

We have conceptualised the economy as a system comprised of a wide range of factors that interact with one another to generate the economic outcomes we see in the region. As we outlined in detail above, there are distinctive internal dynamics within each sub-system, but it is how they interact and reinforce each other that generates the outcomes of the West Midlands economy.

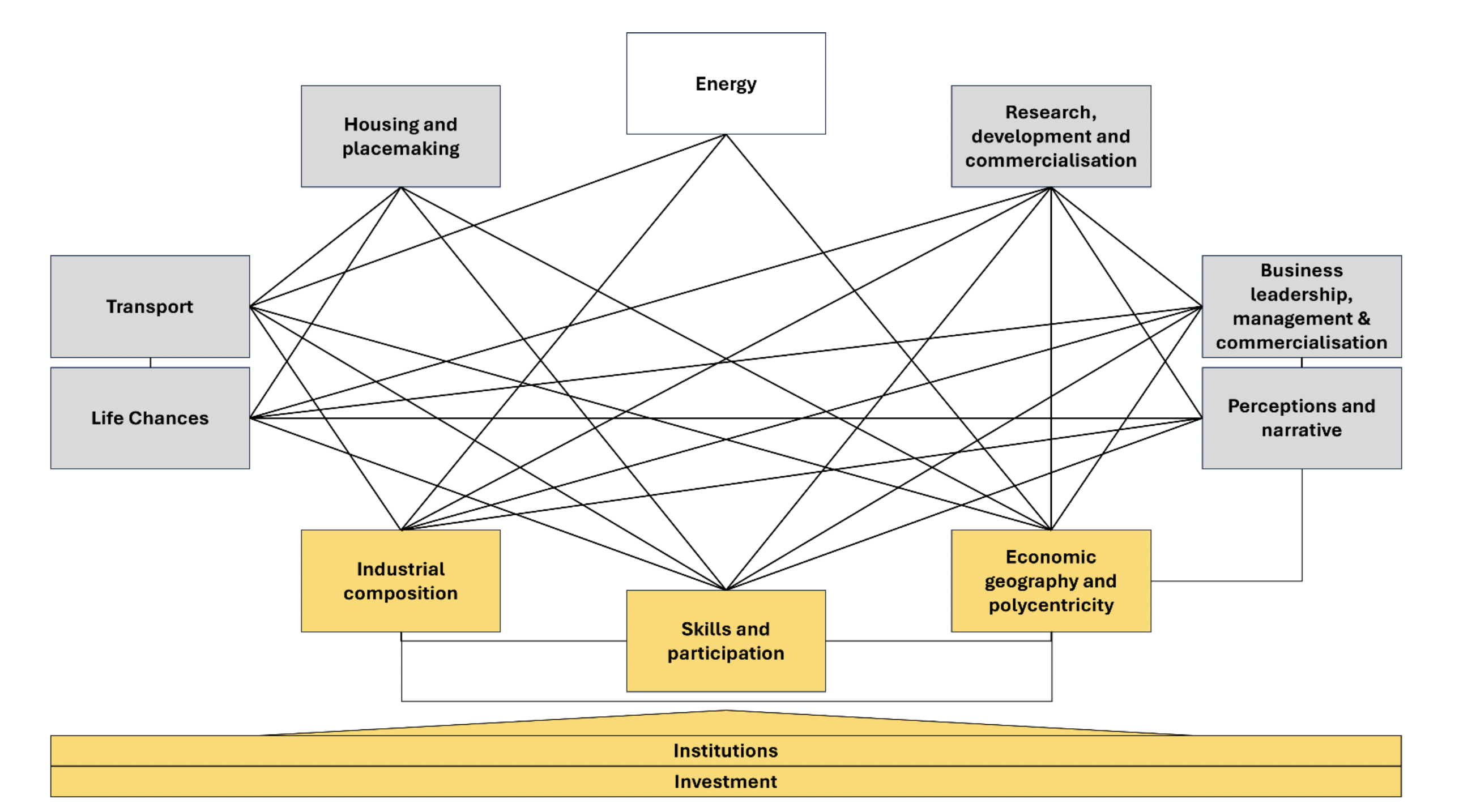

As part of the analysis of each sub-system in section 4, we suggested—in the tables towards the end of each section—what the strong and direct links are between sub-systems to show how they are connected. This allows us to gain greater insight of which sub-systems are most central to our economic system and are therefore more likely crucial to unlocking wider systems change. This analysis shows that the Institutions sub-system is connected with every other sub-system considered, alongside Investment, Skills and Participation and Industrial Composition. The rest, with the exception of Energy, were connected to roughly half of the others. Systems thinking is important because:

- It is how the economy functions in the real world and how economic outcomes are generated.

- It breaks down silos between policy areas, and requires those with policy and investment responsibilities to understand who they depend on and who depends on them, if the West Midlands is to be successful in delivering economic transformation.

- It explains why we need to take an action learning approach to understanding the impact we are making, because it is not clear from the outset exactly how change in one subsystem will affect another and our progress overall—for better or for worse.

- However, connectedness on its own is not necessarily a measure of importance. Further work will need to be done to move from the analysis presented in the theory of growth to a concrete prioritisation.

This analysis shows that the Institutions and the Investment sub-systems are connected with every other sub-system considered. Skills and Participation, Industrial Composition and Economic Geography & Polycentricity are connected with at least three quarters of the other sub-systems. The rest, with the exception of Energy, were connected to roughly half of the others.

Figure 39: subsystem connections.

Sub-systems have different roles in shaping the West Midlands’ economy and the type of growth our vision seeks to generate.

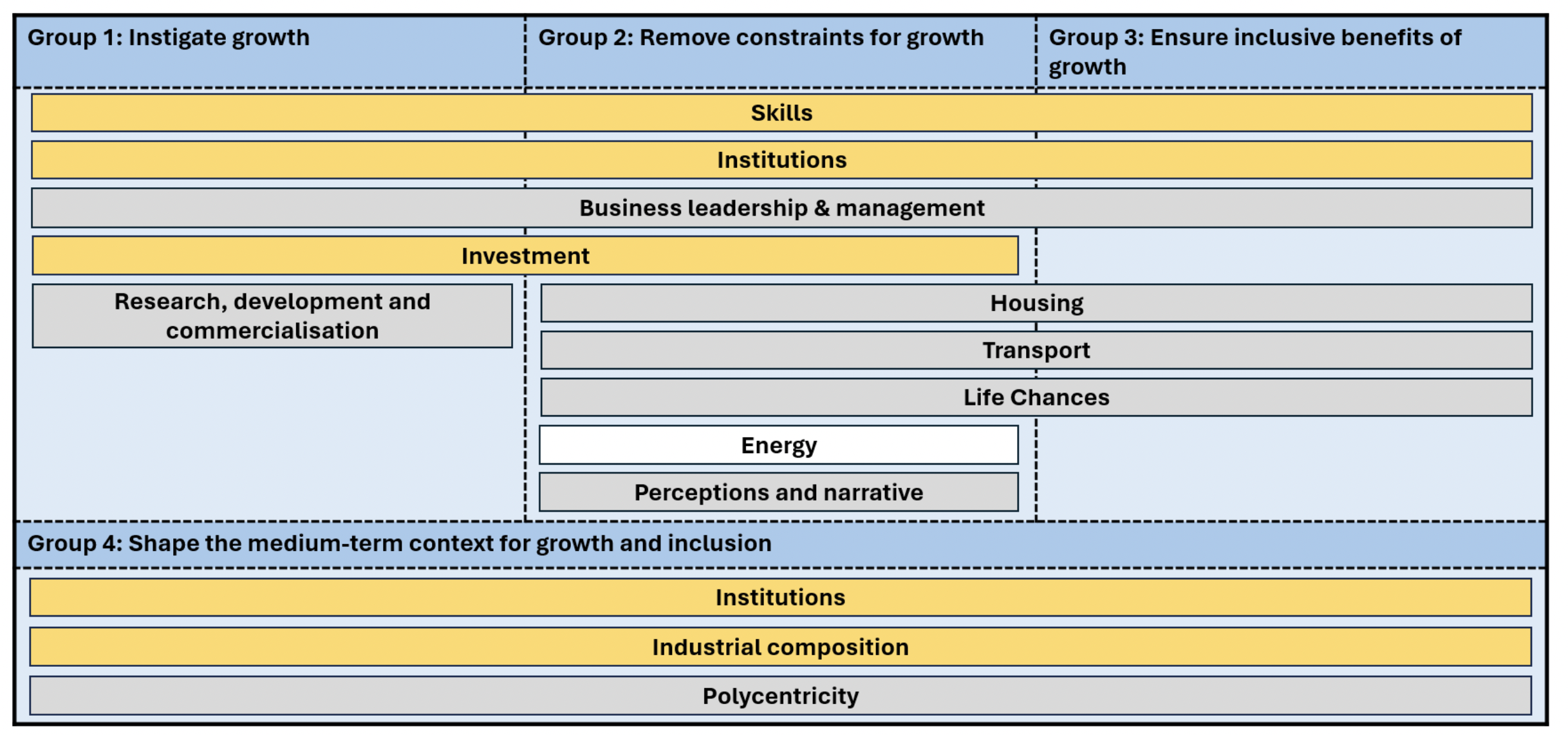

To explore the role that we think each sub-system is playing in this wider system, following the in-depth analysis we have suggested that we can categorise them into four different groups – below – related to boosting growth and economic inclusion. Sub-systems can appear in more than one of these categories as their roles can be multi-faceted. These groups are:

- Sub-systems that need to be addressed to instigate new growth

- Sub-systems that need to be addressed to remove constraints to growth

- Sub-systems that need to be addressed to ensure everyone can benefit from additional growth

- Sub-systems that shape the context the context for the West Midlands and are likely to be consistent for at least the medium term.

The diagram below visualises each sub-system across these groups. We have also retained the colour scheme used in the systems map above so that gold sub-systems are the ones which were most connected, silver the second most connected and white the least connected.

Figure 40: How subsystems sit across different categories.

Lessons from other regions the West Midlands is similar to suggest some factors are particularly important to economic transformation.

Throughout our work on West Midlands Futures over the past year and a half, we have sought to learn the lessons from how other regions have achieved economic transformation—both in the UK and overseas. This has shaped how the West Midlands thinks about economic transformation and how we need to approach it to be successful, based on what has worked elsewhere.

Most recently, this has involved undertaking in-house analysis of which regions are most appropriate for the West Midlands to learn more specific lessons from, based on how similar we are to them across a basket of metrics, which have seen the highest productivity growth and a supplementary qualitative assessment. This analysis suggests the West Midlands has the most to learn from:

- Lille, France. Although the rate of growth in Lille has not exceeded that of France overall, labour productivity in France well exceeds that of the UK. While other places such as Lyon also exhibit some similarities to the WMCA area, Lille is more similar due to its polycentric nature, and a median age that is even younger than Birmingham’s. Additionally, Lille is connected to London and Paris via Eurostar; similar to the potential gains of HS2 for Birmingham. Lille has made significant investment in infrastructure to support the region's strong position as a logistics hub has ensured strong and consistent employment and productivity growth in the logistics sector.

- Greater Porto, Portugal. Porto scores similar to WMCA, is polycentric, and has similarities in its industrial clusters around ICT, automotive. It has seen impressive growth in its sectors, underpinned by a combination of direct funding, fiscal incentives, infrastructure, startup support, and investment promotion. It also plays the role of a “second city” to Lisbon, similar to the West Midland’s role in relation to London.

- Saxony, Germany. Of the German regions, Saxony has seen growth exceeding the national average in 2010 to 2019, as the former East Germany states catch-up. Subsidies to encourage innovation, strong labour market policies and a local digital strategy underpin its’ journey to now being termed ‘the cradle of German mechanical engineering’. The growth rates in other similar places – notably the Ruhrgebiet – has been below the German average in that period; while another potential comparator, the international Meuse-Rhine region, has significantly different governmental set-ups that make it a less appropriate comparator.

- Lombardy, Italy. The region exhibits a very high similarity score, is polycentric (Milan- Bergamo Brescia), and has similarities in its industrial composition. While its regional productivity growth rate, with the exception of Brescia, has lagged behind the average Italian growth rate, there are potentially lessons for both the WMCA area and Lombardy as it seeks to return to growth.

The next phase of our theory of growth will delve further into the details of these examples in particular to help us refine and fitness what needs to be prioritised.

Most importantly, we want to hear from our local, regional and national partners who have a stake in the West Midlands’ economic transformation and ‘test and learn’.

Understanding the evidence and lessons from elsewhere is vital to economic transformation because of just how complex it is, but it only takes us so far. The next phase of developing the West Midlands’ theory of growth will involve testing our assumptions with local, regional and national partners—not just once but over time, to make sure they are and remain relevant. This will involve:

- Testing our vision of what success looks like and our understanding of the specific challenges we have introduced and what needs to change as part of each sub-system, alongside other pertinent and related questions facing the region, as part of the West Midlands Futures Green Paper consultation process. The West Midlands Futures Green Paper consultation process will lead to the production of the West Midlands Growth Plan, a Spatial Development Strategy, further work on Public Service Innovation and a Net Zero Five-Year Plan, drawing on the analysis above.

- Pursing an action-learning approach that will enable us to test our hypotheses, assumptions and real world projects that bring them to life. This means that our theory of growth will continually be revisited, iterated and improved based on the lessons we generate through actions. This will be a key feature of how we convene regional partners beyond the public sector around our vision of economic transformation, so that we can learn the lessons from them.