Foreword

In the West Midlands Growth Plan, the West Midlands Combined Authority has set out its ambition to grow our regional economy and improve living standards for everyone across the West Midlands.

Traditional models of growth often seek to raise prosperity and living standards for some first, before redistributing the fruits of that growth to others, for example, through better public services. In contrast, the West Midlands have committed to a different model approach, Inclusive Growth, where it matters who creates that growth, where it is created, and who benefits from it. In short, we are pursuing Growth for Everyone.

Our Inclusive Growth Framework helps policymakers navigate this complexity, ensuring that people living, working, and visiting the cities, towns, and villages in our region can all play a role in creating prosperity and raising living standards – all while protecting and enhancing our environment.

It does so by aligning all types of investment – public or private, capital and revenue, time and attention – around a shared set of economic, social, and environmental missions. By focusing on these missions – the eight fundamentals of inclusive growth – we can help policymakers understand how a strategy, programme, policy, or activity might impact on other areas, enabling a systems approach to address complex challenges.

Just as the West Midlands Growth Plan is underpinned by a robust evidence base – the West Midlands Theory of Growth – our Inclusive Growth fundamentals are supported by this evidence base. It sets out the enablers and tensions for each fundamental, helping policymakers across the whole policy cycle: from developing and appraising interventions to evaluating their success. Naturally, there are gaps in this evidence base too, offering opportunities for researchers and practitioners to address these gaps and contribute to our areas of research interests.

Together, we can make the West Midlands the best place to live, work, and visit.

Si Chun Lam

Head of Research, Intelligence, and Inclusive Growth

Executive Summary

This report provides essential guidance for policymakers and practitioners across the West Midlands ‘system’, enabling a collective effort to achieve inclusive and sustainable economic growth. By grounding our approach in robust qualitative and quantitative evidence, we can better understand the complex factors that drive prosperity and wellbeing for all our residents, across every city, town, and village.

This report outlines the key enablers and tensions influencing each of our eight inclusive growth fundamentals, offering an analysis of the specific challenges unique to our region. It also highlights the interconnections between these fundamentals, identifying opportunities for collaboration and innovative action across sectors and communities.

Utilising the Inclusive Growth Framework to inform decision-making ensures our strategies and investments are aligned with the needs and aspirations of local people. In strengthening our understanding of the lived experiences of our citizens and communities, we can design and deliver policies that raise living standards, foster resilience, and support the long-term prosperity of our region.

Together, by applying this evidence-based approach, we can drive the transformation required to make the West Midlands a place where everyone can thrive.

Climate and Environment

Greenhouse gas emissions fell by 18% between 2017 and 2022 in the WMCA area, a slightly faster rate than the 15% fall for all of England. This is a priority for our residents, with 61% of those surveyed in 2023 reporting that they had been worried about the impact of climate change over the previous 12 months. The price of not meeting the challenge on climate change is high, with a high emissions projection estimating that temperatures in Central England could reach 5.8 oC higher in 2060-2079 than in 1981-2000. In economic terms, it is estimated that climate change could reduce GVA in the WMCA area by £1.5bn-£2.9bn (around 1.5%-2.9%) a year by 2050.

Domestic energy consumption is generally higher in the WMCA area than the national average, likely due to factors such as variation in energy efficiency of housing, and cold temperatures. An estimated 17.9% of residents were living in fuel poverty in 2023, making it a priority to increase the energy efficiency of homes to reduce the burden of heating costs. Not only is there a clear benefit for residents financially, but domestic emissions also contribute an estimated 100 million tonnes per year in England, with gas heating largely to blame. The WMCA estimates that their goal of retrofitting a million homes by 2041 would reduce our contribution to this by around 4 million tonnes.

There has been a significant reduction in the proportion of waste sent to the landfill in England, with a sharp fall from 30.9% in 2013/14 to 5.5% in 2023/24, due to various changes including an increase in recycling, alternative methods of disposal due to the landfill tax, and improved product design reducing wastage. In the WMCA area, an even lower proportion of waste goes to the landfill, at 3.6%. This is important because landfills are harmful to the environment and health of local communities. Whilst our traditional economic system has been quite linear, with resources harvested, refined, consumed and discarded, designing a circular economy where resources are reused reduces demand, extends value and reduces emissions.

The estimated almost 5 million trees in the WMCA area capture around 57,620 tonnes of CO2 every year, with their contribution to our environment having an estimated value of nearly £75m. In addition to environmental benefits, access to green spaces is associated with improved mental health and increased life expectancy. The health benefits of living with a view of a green space are worth up to £300 per person per year, with close proximity to a park increasing a property’s value by an estimated 9.5%. Our green spaces not only absorb CO2, but they can also serve as drainage systems, providing a significant reduction to the level of surface water pollution. The summer floods of 2007 cost an estimated £3.2bn, highlighting the value to the economy.

Inclusive Economy

Traditional economic measures often focus on the growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross Value Added (GVA) to measure the health of the economy. Unfortunately, even when these measures are increasing, growth is not equally distributed. Research has found that economic growth did little to reduce poverty between 2000-2008, with top earners seeing their wages increase but those in the bottom half of earners seeing little change. Between 2008-2022 the gap between high and middle earners widened whilst the gap between middle and low earners narrowed, meaning that whilst inequality has reduced, the top earners have increased their share at a higher rate. The higher rate of inequality in the UK compared to 23 OECD countries cost the country approximately £106.2bn in 2023 in health and crime alone. American Research has found that eliminating wealth inequality increases consumer spending and economic participation, improving living standards and increasing economic stability.

Inequality in economic activity and employment based on gender and ethnicity result in worse outcomes for less privileged groups, ultimately harming the economy. The WMCA area also has a larger than average proportion of economically inactive residents who are on long term sick, with 30.5% of those inactive in this category compared to 26.3% nationally, making this a priority group to support. Young people are another group requiring support, with 16.3% of 16–24-year-olds unemployed in the WMCA area, compared to 11.8% in Greater Manchester. Research has found that each month of unemployment between 18 and 20 reduces a person’s income by around 1.2% permanently, representing the scarring effect on young people.

Business birth rates fell by around 13% in England in between 2021-23, but they fell by 23% in the West Midlands region. Not only are less businesses being created, but the West Midlands region also has the worst 5-year business survival rate in the UK, with only 34.7% of those created in 2018 still operating in 2023. Whilst the wider economy has suffered from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years, another prominent challenge for the region is in workforce skills, with 35% of vacancies considered hard-to-fill in 2022 due to skills shortages.

Power and Participation

Turnout at elections is the most common traditional measure of participation, as it gives residents the opportunity to choose who represents them. In the 2024 general election, only 57.3% of eligible voters cast their ballot in the West Midlands region, less than the 59.7% nationally. The turnout in local elections is lower, with only 29.8% voting in the 2024 mayoral election in the WMCA area, showing the different level of engagement residents have with us.

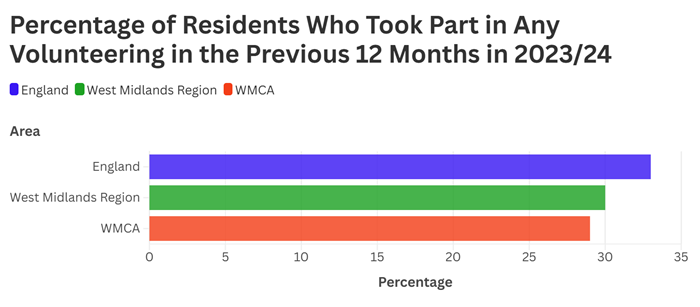

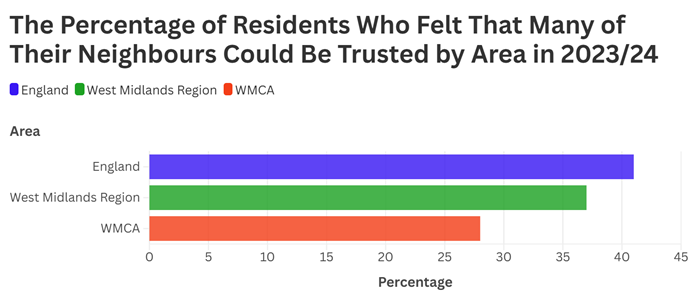

Only 25% of residents in the WMCA area felt that they could personally influence decisions affecting their local area in 2023/24, but only 29% agreed that they would like to be more involved in decisions made by their council. Residents in our area were also less likely to report any civic participation in the previous 12 months than nationally, with only 29% compared to 33%, but volunteering represented a much more common method of engagement, at 51%. Research shows that volunteers report higher levels of community identification and social support, but only 28% of WMCA residents trust many of their neighbours, much less than the 41% English average.

A survey from the LGA in 2021/22 found that only 16% of residents in the West Midlands region reported trust in the national government to make decisions about services in their local area, with a far higher 71% trusting their local council. Measuring trust is challenging, relying on surveys which often have small sample sizes, and so further research could help increase our understanding of why residents feel this way.

Affordable and Safe Places

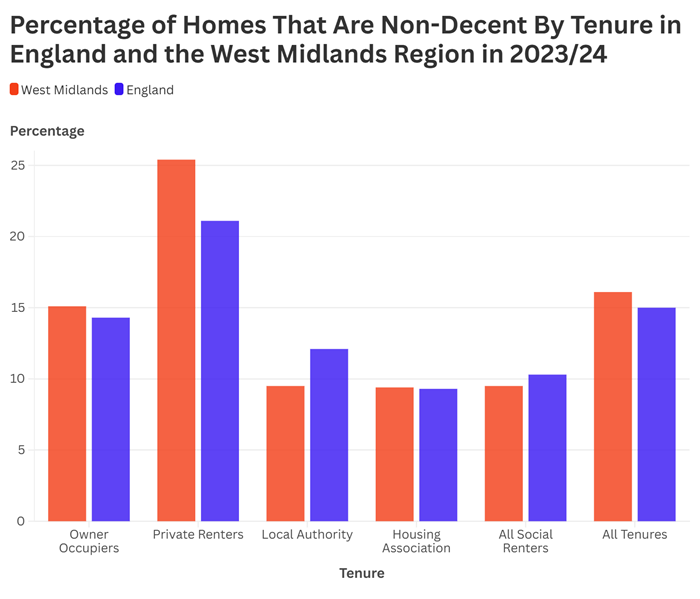

The West Midlands region had one of the highest proportions of homes that are non-decent in 2023 at 16.1%, with 25.4% of privately rented homes in this category. Homes in the WMCA area were more likely to be overcrowded in 2021, with 7.8% of homes, 1.4pp more than the English average, with ethnic minorities more likely to be impacted. Living in an overcrowded home is associated with worse mental health, with children also struggling to find space to study and complete homework. Around 1.5 million children in England lived in non-decent homes in 2022-23, with around 1 million of those living in hazardous homes, and nearly 800,000 living with damp. The median cost per household to rectify these issues was lowest in the West Midlands region, at £6,408.

Damp in a child’s bedroom is associated with respiratory problems, a situation that is more likely in homes living in fuel poverty as damp can be exacerbated by restricted heating. The increased risk of mould in these homes presents an additional cost to rectify, and a health challenge for those who are already living in poverty.

In 2023/24, 17,310 households in the WMCA area were assessed as being due a homelessness duty, with ethnic minorities more likely to be impacted. At the end of March 2024, there were 6,520 households living in temporary accommodation, with 5,537 including children. Local authority and housing association stock only housed 40% of these households, highlighting that the supply cannot meet the demand. Shelter estimated that local councils spent £2.3bn in 2023/24 on providing temporary accommodation. Hospital records show that the median age of death for people rough sleeping in England was 20 years younger than non-rough sleepers admitted who were in the most deprive quintile. The ratio of house prices to earnings increased from 5.72 to 7.1 in the West Midlands region between 2013 and 2023, increasing the financial pressure on residents.

The level of crime rose in the WMCA area in many categories between May 2020 and December 2024, including violent crime, shoplifting, possession of weapons and public order offences. Anti-social behaviour fell from 8,340 to 1,992 between December 2010 and December 2024. It can be challenging to draw interpretations from these figures, as a reduction can reflect reporting differences rather than reduction in crime. Residents who feel safe in their community tend to walk more, which is beneficial for both their health and the environment.

Connected Communities

53.1% of drivers surveyed in the WMCA area reported that they would find it difficult to work without access to a private vehicle. This is a large proportion, but it was the lowest of any metropolitan area outside of London. The most common difficulty reported by residents using public transport or active travel to commute in 2022 was quality. Around 11.9% of residents in the West Midlands region live in transport poverty. As cars are the most expensive mode of transport, affordable and high-quality public transport is a priority for those in poverty. Households in the top 3 income quintiles have similar levels of car ownership but the level drops considerably for the fourth and fifth quintiles. TfWM reported that residents with cars could access more than double the job opportunities within 45 minutes than those without a car. 1 in 4 households in the West Midlands don’t have access to a car, limiting their employment opportunities. In England, those with mobility issues were more likely to choose the bus than rail but still made 38% fewer trips than those without mobility issues. Reasons cited for low train use amongst this group include distance to stations, platform design, unclear signage and announcements, and difficulty boarding and using seating.

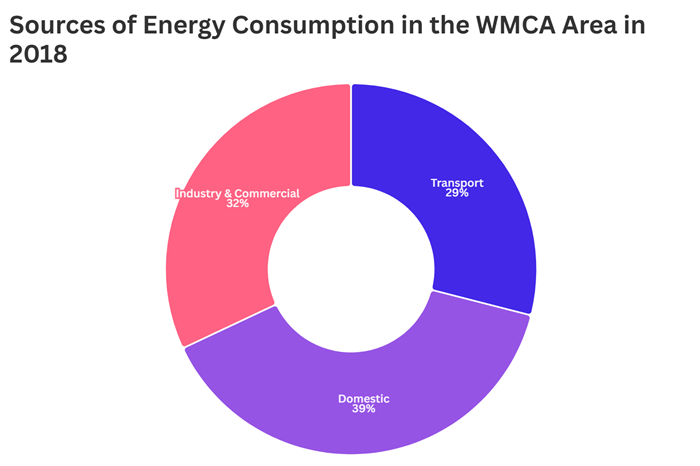

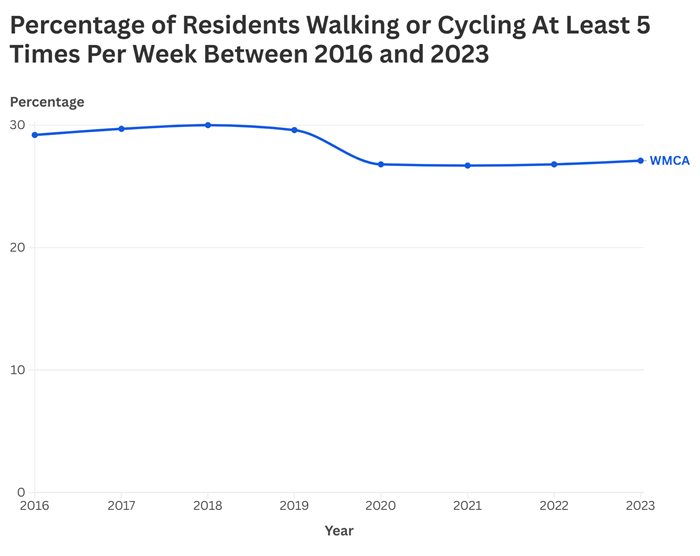

In 2018, it was estimated that 29% of all energy consumption in the WMCA area came from transport. Cars contributed around 57% of greenhouse gas emissions from road transport in 2021, highlighting the importance for environmentally friendly alternatives. The University of Birmingham estimated that improving air quality in the region to meet WHO guidelines could save as much as £3.2bn over 20 years due to improved health outcomes. Active travel presents an alternative, but the proportion of adults walking or cycling at least 5 times a week fell from 29.6% in 2019 to 26.8% in 2020. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, this figure has remained reduced. It is estimated that if all regions in England walked and cycled as much as the most active region, around 1,800 early deaths a year would be prevented.

Access to digital connectivity is of ever-increasing importance. The Lloyds Consumer Digital Index found in 2024 that the proportion of those digitally excluded had fallen to 3% nationally. Digital exclusion limits residents’ ability to access cheaper goods and services, costing an estimated £478 per year on average. It also presents a barrier in applying to jobs and accessing educational resources and courses. There are a range of causes of digital exclusion, including cost of devices and broadband, lack of digital skills, and data privacy concerns. Research in 2022 found that every pound invested in building digital skills of excluded people returned £9.48, worth an estimated £12.2bn nationally.

Education and learning

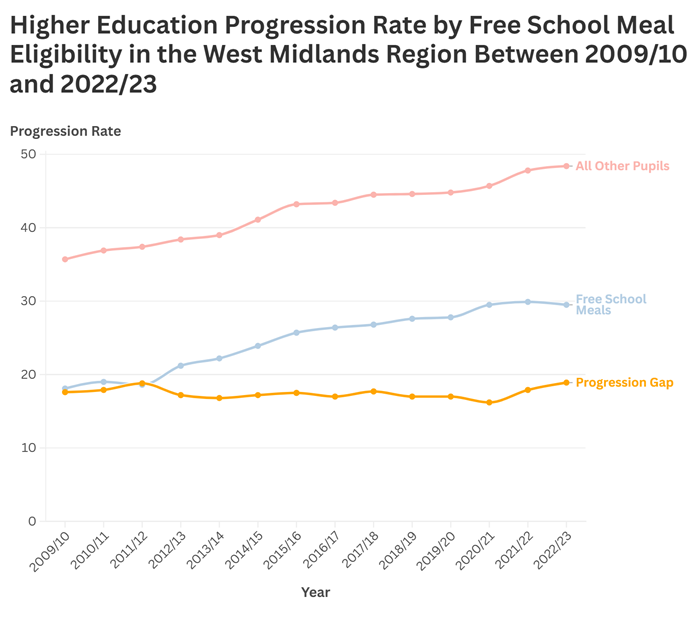

The WMCA area has the lowest proportion of working age residents with a level 3 qualification. Despite this, the proportion of vacancies due to a lack of skills, qualifications and experience was lower than the national average. The gap between the rate of pupils on free school meals and their peers progressing on to higher education in the West Midlands has widened and is now at its widest since before 2009 when the earliest data is available. Analysis of OECD countries found that the rate of university education had the strongest influence on life expectancy in a country, highlighting the importance of this.

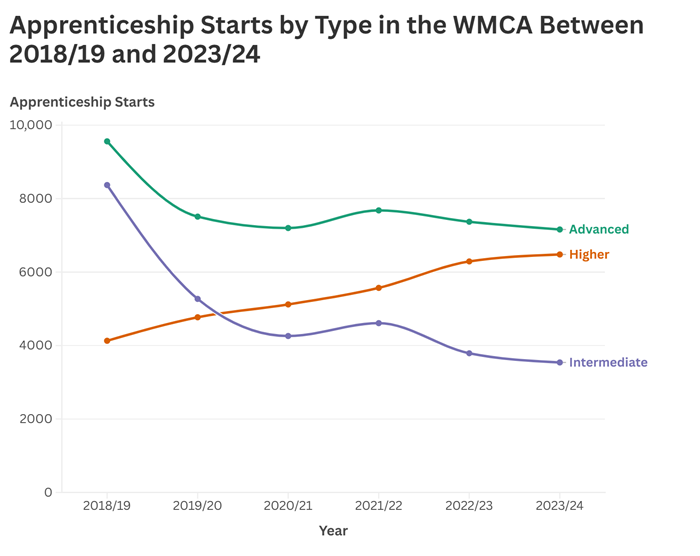

Apprenticeship starts have fallen at a faster rate than the national average. Level 3 apprenticeships particularly benefit young men, providing earnings more than 40% higher than those who studied an equivalent classroom-based qualification at the age of 23. Degree apprenticeships have fared better, but only 5% of students on these courses were eligible for free school meals, compared to 17% for regular degrees, and the completion rate was only 55%, far less than the 89% of traditional degrees.

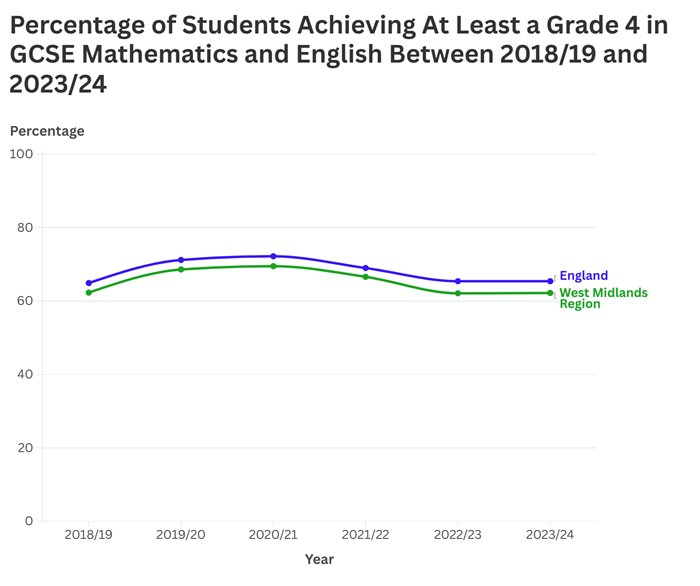

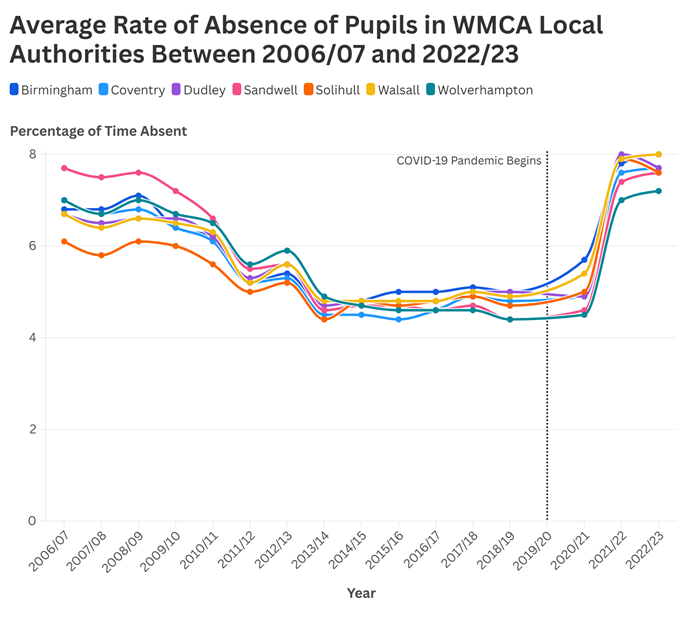

Pupils in the region miss more school and are less likely to achieve the required standard in their Maths and English GCSEs than the rest of England. There was a considerable variation in achievement by ethnicity, and by SEN status. This data can help inform where adult education programmes can have the largest impact in the future.

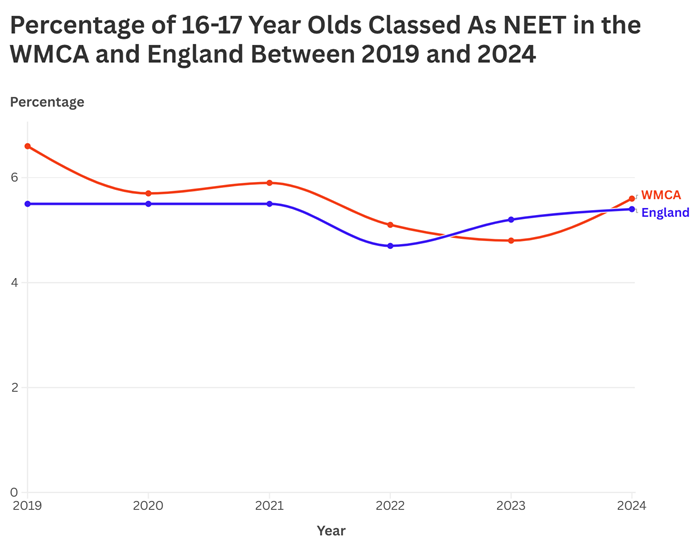

The rate of young people who are NEET is slightly higher in the WMCA area than the national average. Research found that each month of unemployment between the ages of 18 and 20 results in a permanent income loss of 1.2% per year but when workers reach 24, any unemployment does not have a visible impact.

Health and Wellbeing

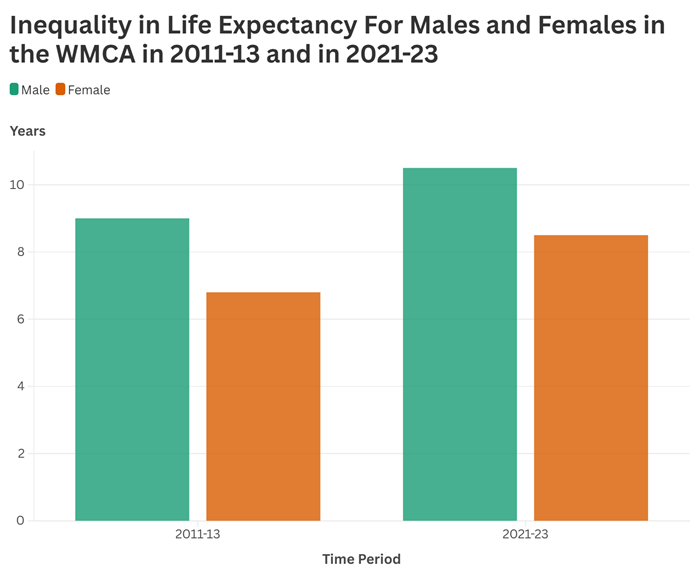

The inequality in life expectancy in the West Midlands region was 10.5 years for males and 8.5 years for females between 2021 and 2023. Research has also shown that the more deprived a background a child or young person comes from, the more likely they are to received emergency admissions for conditions including asthma and diabetes. Another research study also found that someone dies every 10 minutes in England due to inequality, with a total loss of life expectancy of 3.3 years for those aged under 75.

Analysis by the ONS found that self-reported health, marital status (with those married or in a civil partnership better off) and employment status were the largest contributors to life satisfaction. Between 2017 and 2023, there was a sharp rise in estimates of mental health conditions amongst 17- to 19-year-olds, with an increase in child mental health services demand of 50%. Demand on adult mental health services has also risen across England. A major cause of this is loneliness, making a person 2.25 times more likely to have a depression diagnosis. In 2022, those reporting mental health issues were estimated to have a 17.15% lower salary on average.

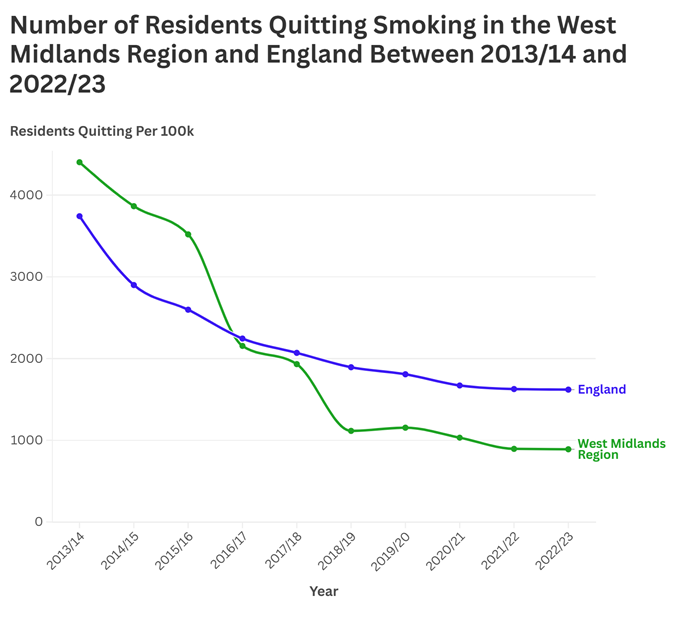

Smoking remains the largest preventable cause of cancer in England, with an estimated 12% of adults smoking in the West Midlands region in 2023. Despite this, the proportion of smokers quitting for 4 weeks or more has fallen sharply from 4.4% in 2013/14 to 0.9% in 2022/23. Research published in 2024 estimated the cost of smoking to the NHS to be £1.9bn, with £21.8bn lost in reduced productivity. Estimates show that men living in the most polluted neighbourhoods outside of London will live 3.5 years less, with women living 2.5 years less. Obesity presents another public health issue, costing the NHS an estimated £6.5bn per year. The level of obesity in the UK more than doubled between 1993 and 2022, and obesity in children significantly increases their risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in later life.

Equality

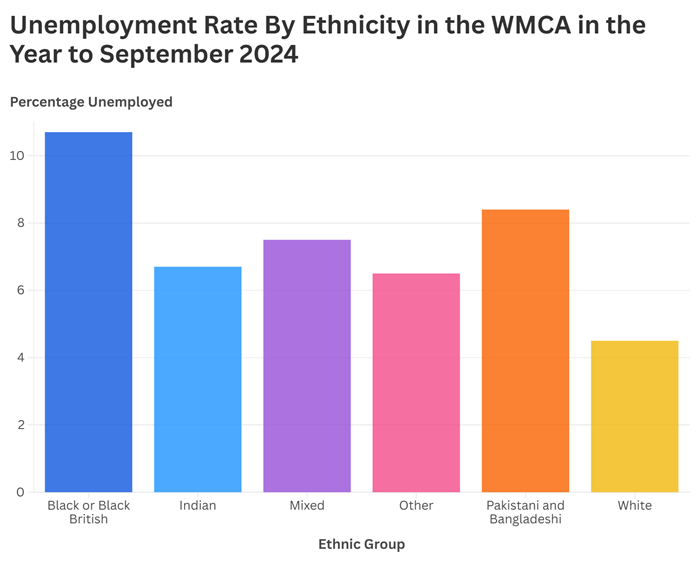

Different societal groups in the WMCA area have varied experiences of pay and employment. In the West Midlands region, there was an estimated race pay gap of 9.5% in 2022, disability pay gap of 17.7% in 2023, and gender pay gap of 12% in 2024. Unemployment rates varied by ethnicity in the WMCA area, at 4.5% for White residents compared to 10.7% for Black residents in September 2024. Only 3.7% of employed ethnic minorities in the WMCA area were working in managerial or senior official occupations in March 2024, compared to 8.7% nationally.

Women are more likely than men to work part time, be employed on zero hours contracts, and be classed as low earners. In the WMCA area the lower economic activity rate of women resulted in a loss of 8.35% of GVA in 2023. Childcare costs in the UK were the second highest in the OECD in 2022, costing around one in three parents of pre-school children a third of their wages.

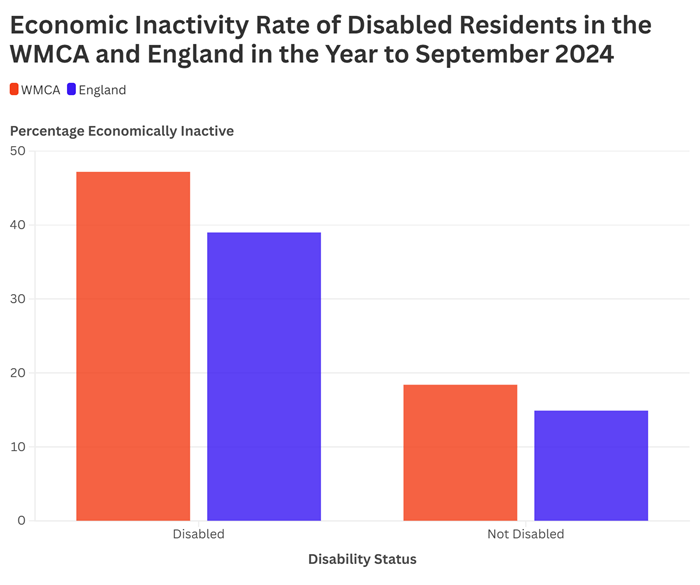

The unemployment rate of disabled residents in the WMCA area is almost double that of non-disabled residents. There is an even larger inequality in rates of economic inactivity, at 47.2% for disabled residents compared to 18.4%, contributing to increased levels of poverty amongst disabled people in the UK. There is an estimated ‘Disability Price Tag’ of £1,010 per month in the UK in 2023 for a disabled household to achieve the same standard of living as a non-disabled household. Disabled residents in the WMCA area with mobility issues also have less choice in homes, with an estimated 28% of housing unable to meet accessibility standards.

White British residents in Britain spent the lowest proportion of their income on housing in 2021/22-2022/23 at 11%, compared to Arab residents who spent the highest at 26%. Ethnic minority households are also more likely to not have access to a car or van than White households, with 34% of mixed ethnicity residents compared to 16% of White residents.

Introduction

The WMCA defines Inclusive Growth as ‘a more deliberate and socially purposeful model of economic growth - measured not only by how fast or aggressive it is; but also, by how well it is created and shared across the whole population and place, and by the social and environmental outcomes it realises for our people’. The Inclusive Growth Framework has been at the core of the WMCA’s work since it was approved by the WMCA board in September 2018. Since then, it has shaped the development of strategy and policy to ensure that we deliver economic growth in a sustainable way that benefits all of our residents.

Figure 1: A circular infographic illustrating the concept of inclusive growth, with an outer ring representing the planetary boundary and climate and environment fundamental, and an inner ring representing the seven social foundation fundamentals

The framework consists of 8 fundamentals: climate and environment, which focuses on our role in minimising climate change and other environmental impacts in everything we do, and 7 human-focused fundamentals, representing a range of equally important priorities to our residents. Although we recognise 8 individual fundamentals, the message that they are interconnected is central to the purpose of the framework.

Our use of traditional measures of economic growth such as GDP are important, but they only capture part of the picture. We must also understand who is creating economic growth, how that growth is distributed amongst our residents and the progress we are making to improving social and environmental outcomes in our region. Through the lens of inclusive growth, we can ensure that we are incorporating these issues into our decision-making, making our policy more informed and effective.

The funding landscape has often led to narrow and focused policy making that has encouraged competition and trade-offs. The Inclusive Growth approach emphasises that peoples’ experiences of the economy are complex and so encourages policy makers to broaden considerations to all eight of the fundamentals when designing policy. Whilst the Inclusive Growth framework provides us with a basis to track our impact, we must also understand the challenges that our region faces within each fundamental and how these influence our residents.

Breaking down each fundamental into defined scopes allows us to consider the key issues and measure their impact. By harnessing the data available to us we can identify where barriers are most profound for our residents, which can aid us in determining our priorities. Combining these insights with research not only develops our understanding of people’s lived experiences, but it also provides us with the evidence we need to make effective decisions and develop strategies that capture the complexity of our economy.

Methodology

For each fundamental of inclusive growth, colleagues within the WMCA were asked to provide sources of research and analysis that could form part of this evidence base. The sources provided were then collated and informed the content of this document where they could provide relevant insights. Sources which provided information about the WMCA area, or the wider West Midlands region were prioritised; where research or data was not available at either of these levels, more general national level data was used to address any gaps in content. Secondary analysis was used in producing the figures for this document, from a range of sources including government statistical publications, reports and datasets, along with other public sector and charity commissioned reports.

The content for each section was written with the aim of providing a wide coverage of each inclusive growth fundamental’s scopes. Each section contains a range of more traditional and wider measures, with a narrative of what they tell us about the challenges and opportunities we have in the West Midlands.

Climate and Environment

Introduction

Climate and Environment is the capacity to which our social and economic ecosystems can cope with the multiple risks, uncertainty and threats posed by climate change. We must change our social and economic ecosystems to ensure we work within the planet’s limits and make adaptations which increase our ability to cope with the risks, uncertainties, and threats associated with climate change. The pursuit of continuous growth is not sustainable if we use up natural resources faster than the Earth can renew them.

Economic prosperity and the condition of the natural environment are intrinsically linked. Unlocking investment for the environment and nature-based solutions will support WMCA in delivering its ambition of a region which is fairer, greener, healthier, better connected, and more prosperous.

Climate Resilience

Traditional Measures

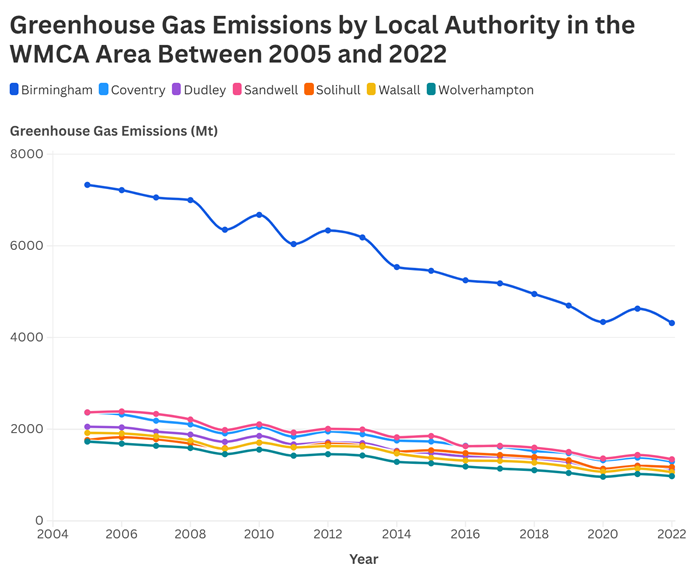

The level of greenhouse gas emissions is commonly measured to understand our contribution to climate change. In 2022, an estimated 291 Megatonnes (Mt) of emissions were generated in England, with around 32Mt of these generated in the West Midlands region.[1] Emissions from the WMCA area totalled around 11Mt. Although the emissions per capita for the WMCA are only around two thirds of that for the wider region, the emissions per km2 were five times as much, which demonstrates how differently emissions are distributed in metropolitan areas. Compared to 2017, the 11Mt for the WMCA area represents a decrease of approximately 18%, slightly more than the national decrease of 15%.

[1] Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, “UK Local Authority and Regional Greenhouse Gas Emissions Statistics: 2005 to 2022”

Figure 2: A line graph showing a trend of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by local authority in the WMCA between 2005 and 2022

Further Measures and Research

Climate change is an important issue to residents in the West Midlands region, with around 61% in 2023 reporting that they had been worried about the impact of climate change over the previous 12 months though this is a slightly lower level than the 64% in England.[1] In recent years there has been a visible impact on weather conditions in the West Midlands and wider society attributable to climate change. There has been an increased frequency and severity of heatwaves, which pose a health threat to those who are vulnerable. Research in Dudley has shown a trend of increasing heatwaves between 2012 and 2022, along with a similar pattern of increased excess deaths.[2] Excess deaths related to heatwaves have been found to be more focused in urban areas, suggesting that areas within Birmingham, Coventry and parts of the Black Country are more likely to be impacted.[3] The WMCA’s Climate Risk and Vulnerability Assessment shows that those in more deprived, urban areas are more vulnerable to the impact of climate change in the West Midlands.[4]

UK Climate Change Projections from 2018 show that even if emissions are brought to a low level, a summer in central England between 2060-2079 could be as much as 3.3 oC warmer than between 1981-2000.[5] A high emissions scenario could see temperatures rise as much as 5.8 oC, highlighting the importance of lowering emissions to limit the risks these rises present. A summary of climate change impacts in the West Midlands reports that an absolute best-case scenario could still see a 2.3 oC rise in summer temperatures, along with wetter winters, drier summers and increased humidity throughout the year.[6] This demonstrates the scale of temperature increases and the risks that increased heat presents to human life as well as to critical infrastructure and the natural environment. The 2022 summer heatwaves brought 125 faults to National Grid’s power distribution in the West Midlands, affecting 46,225 customers.[7] Storm Darragh in December 2024 brought significant disruption to transport in the West Midlands, with rail services suspended between Walsall and Wolverhampton due to obstructions on the line and an estimated 200 trees falling down in Birmingham alone.[8]

To minimise further climate change, the WMCA declared a climate emergency in 2019 and has committed to making the West Midlands net zero by 2041, meaning that CO2 emissions produced in the region must be reduced to a level where they are balanced by emissions removal.[9] This requires both reducing emissions and increasing our capacity to remove emissions from the atmosphere.[10] To reduce the impacts of climate change, the WMCA is committed to climate adaptation - making adjustments to the way we do things so that our region is climate resilient. Climate resilience means our communities, infrastructure and natural environment can withstand, cope with and bounce back from the impacts of a changing climate. The economic impact of failing to do this for the West Midlands would be severe, with climate change projected to reduce GVA by £1.5bn-£2.9bn (around 1.5%-2.9%) per year by 2050 due to factors including increased damage from flooding, decreased water availability and the impact of increased heat.[11]

[1] Office for National Statistics, “Climate Change Insights, Families and Households”

[2] Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council, “Heatwave Briefing: November 2022”

[3] Gasparrini, et al. “Temperature-Related Mortality Risks in England”

[4] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Climate Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (CRVA)”

[5] Met Office, “UKCP18 Infographic: Headline Findings – Land”

[6] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Summary of Climate Change Impacts in WMCA Area”

[7] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Economic Impacts Assessment Executive Summary”

[8] Majid Mahmood, “We’ve published our climate adaptation strategy for the West Midlands”

[9] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Environment and Energy”

[10] National Grid, “What Is Net Zero?”

[11] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Economic Impacts Assessment Executive Summary”

Energy Usage

Traditional Measures

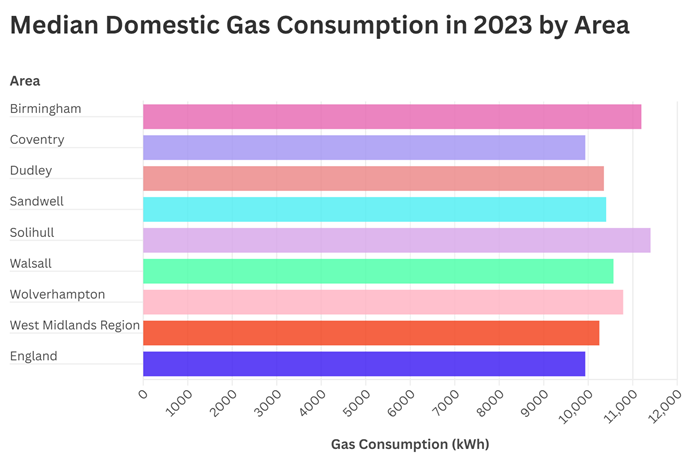

The median consumption of domestic gas in England in 2023 was around 9,900kWh.[1] Other than Coventry, which was around the same, all local authorities in the WMCA area had a median consumption rate above the national average. Multiple factors influence the rate of consumption in different areas, including the energy efficiency of housing, and variance in cold temperatures.

[2] This is likely to be behind the higher levels recorded in the WMCA area.

[1] Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, “Regional and Local Authority Gas Consumption Statistics.”

[2] Mashhoodi, “Who is more dependent on gas consumption? Income, gender, age, and urbanity impacts”

Figure 3: A bar chart comparing the median domestic gas consumption of local authorities in WMCA to the West Midlands region and England in 2023, with only Coventry’s figure below the regional and national average

Further Measures and Research

A large amount of CO2 emissions is generated domestically, with an estimated 100 million tonnes emitted each year in England, averaging around 4 tonnes per household.[1] Gas heating makes a significant contribution to this. To address this issue, the WMCA has committed to retrofitting over one million homes in the region by 2041, with the outcome being an estimated reduction of more than 4 million tonnes of emissions.[2] Not only are there clear environmental benefits from this, the increased energy efficiency will reduce energy bills, providing much needed financial relief for those living in fuel poverty, which 17.9% of households in the WMCA area experienced in 2023.[3] The WMCA estimates that its current retrofit programmes can deliver fuel savings of £91m per year for residents. Further benefits include the creation of 6,000 skilled jobs and an increase of £10.8bn in GDP.[4] These interventions can maximise the benefits to the environment, skills in the workforce, and improve living standards for residents.

[1] Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, “English Housing Survey: 2022 to 2023 Energy Report”

[2] West Midlands Combined Authority, “West Midlands Levelling Up Growth Prospectus: Section A – Going Further, Faster – Retrofit”

[3] UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, “Fuel Poverty Detailed Tables 2025 (2023 Data)”

[4] West Midlands Combined Authority, “West Midlands Levelling Up Growth Prospectus: Section A – Going Further, Faster – Retrofit”

Circular Economy

Traditional Measures

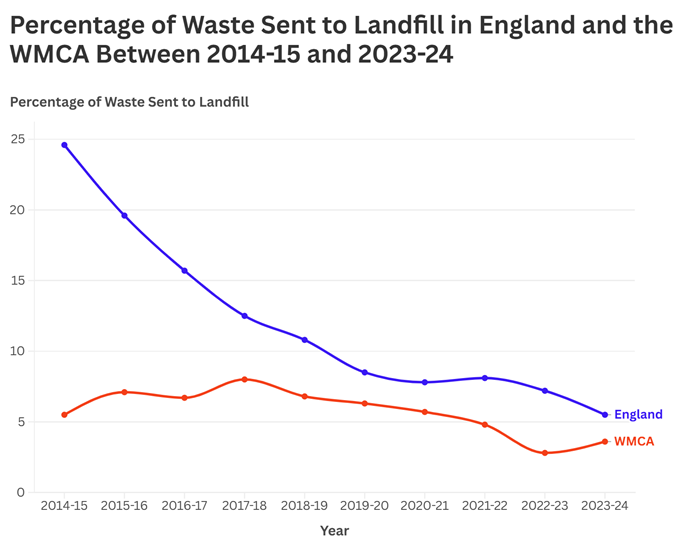

In 2023/24, around 5.5% of all Local Authority collected waste in England was sent to the landfill.[1] This is a significant reduction on the rate of 30.9% in 2013/14. The rate was lower in the West Midlands region, at 4%, and even lower in the WMCA area, at 3.6%. The large reduction in waste going to landfill in recent years is down to various factors, including increased uptake in recycling, moves to alternative disposal methods in response to the landfill tax, and improved product design.[2] The landfill tax is an additional charge to businesses who dispose waste using landfills, with the cost determined by the weight of the waste.[3] Landfills are harmful to both the environment and the health of communities, producing both greenhouse gas emissions and other emissions which can be toxic to humans.[4]

[1] Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, “Local Authority Collected Waste Management – Annual Results”

[2] Slorach et al, “Assessing the economic and environmental sustainability of household food waste management in the UK: Current situation and future scenarios”; Waste Managed, “UK Landfill Impact Guide 2025”

[3] UK Government, "Landfill Tax"

[4] Dirk, "Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts of Landfills"

Figure 4: A line graph showing the percentage of waste sent to landfill in England and the WMCA between 2014-15 and 2023-24, with WMCA consistently sending less than the national average

Further Measures and Research

Whilst gas heating is a key contributor to CO2 emissions in the West Midlands, a significant amount can also be attributed to the linear design of our economy, where resources are utilised in an unsustainable manner. In our current economic system, a large amount of resources are used to create products which are then used and discarded, becoming waste.[1] Designing a circular economy where we reuse resources, reduces the demand for new resources and extends the value of resources which would otherwise be disposed of or combusted and increase emissions. The WMCA estimated in 2022 that engaging 200 businesses a year in a waste management programme could reduce carbon emissions by 14,000 tonnes a year and increase GVA by £1.8m.[2] The potential benefits are large, with an estimated 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions generated through manufacturing possible with more circular processes.[3]

Policymakers should consider where their work can contribute to developing a circular economy – with particular focus on reducing the amount of waste that goes to landfill. Working with businesses in the local area to identify processes that can be made more sustainable through increased recycling and waste disposal could be key to reducing the environmental impact of our waste, improve our residents’ health and improve the local economy.

[1] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, "What Is the Linear Economy?"

[2] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Circular Economy Routemap 2024”

[3] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Circular Economy Routemap 2024”

Biodiversity

Traditional Measures

Reducing emissions is a significant priority for the region to reduce our impact on the environment, and the benefits of this can be improved through increasing our capacity to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. Trees provide a large contribution to this, with the estimated 4,918,000 trees in the WMCA area capturing around 57,620 tonnes of CO2 every year.[1] The economic benefits of our ecosystem’s contribution to the environment are estimated to be worth around £73,446,000 a year. This contribution includes reducing air pollution which is detrimental to our residents’ health.

Further Measures and Research

Access to green spaces is associated with improved mental health and increased life expectancy, although other factors influence this as those living in deprived areas are also likely to have poorer access to these spaces.[2] The health benefits of living with a view of green space are worth up to £300 per person per year, another example of the strong relationship between our environment and our health.[3] It is also estimated that close proximity to a park increases a property’s value by 9.5%.[4]

A biodiversity net gain of 10% is mandatory for developers in England, meaning that the amount and quality of natural habitats are improved after a development.[5] This is crucial to sustain eco-systems in our region, and to maintain the quality of our natural environment. Our green spaces not only absorb CO2, they can also serve as nature-based solutions to our changing climate, such as nature-based sustainable drainage systems (NbSuDS). These can provide a significant reduction to the level of surface water pollution and mitigate the impact of flooding. 13 lives were lost during the summer floods of 2007, with two thirds of the flooding attributed to surface water, and an estimated cost of £3.2bn.[6]

[1] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Valuing the West Midland’s Urban Forest”

[2] Health Foundation, "Relationship Between Access to Green Space and Health"

[3] West Midlands Combined Authority, “West Midlands Natural Environment Plan 2021–2026: Access to Green and Blue Spaces”

[4] UK Green Building Council, “Nature-Based Solutions to the Climate Emergency”

[5] Environment Act, 2021, c.30 (UK): section 98, para. 2.3.

[6] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Nature Based SuDS Guidance Document”

Air Quality

Traditional Measures

The impacts of climate change are not only felt in our environment and through weather patterns. Air pollution in the form of particulate matter is produced by carbon emitting processes such as car engines and domestic combustion, damaging both the environment and human health.[1] Of particular concern are particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 microns, referred to as PM2.5.[2] The amount of PM2.5 pollution is measured at various sites in the UK, a few of which are located in the WMCA area. Urban sites located in Birmingham Ladywood and Coventry Allesley did not record any levels of moderate or high pollution for any hours in 2023, a considerable improvement from a total of 414 hours in 2019 at the two sites.[3] A roadside monitor on the A4540 in Birmingham also did not record any moderate or high pollution in 2023, a level it has now maintained for 3 consecutive years.

Further Measures and Research

Exposure to PM2.5 is associated with increased deaths from cardiovascular disease, along with deaths related to hypertension and diabetes.[4] Research by the University of Birmingham has shown that up to 2,300 people die early due to long term exposure to air pollution every year in the West Midlands.[5] The scale of this impact is large, with a study in 2018 forecasting a cost of £5.56bn to the NHS between 2017 and 2025 due to around 1.15m cases of disease linked to air pollution.[6] The article also acknowledges that this figure would be higher if including diseases for which there is less robust evidence finding a link to air pollution. To reduce the levels of PM2.5 generated, the West Midlands is working to reduce domestic solid fuel combustion, which research suggests would reduce the level of PM2.5 by 13.4%.[7] The same research found that a reduction in road transport and agriculture emissions at a national level would reduce PM2.5 by 29%.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme, “Air Pollution and Climate Change: Two Sides of the Same Coin”

[2] Yang et al., “Trends on PM2.5 Research, 1997–2016: A Bibliometric Study”

[3] Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, “Air Quality Statistics: ENV02 Dataset”

[4] Pope et al., “Relationships Between Fine Particulate Air Pollution, Cardiometabolic Disorders, and Cardiovascular Mortality”

[5] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Air Quality”

[6] Pimpin, Laura et al., “Estimating the Costs of Air Pollution to the National Health Service and Social Care: An Assessment and Forecast up to 2035”

[7] Mazzeo et al., “Modelling the Impact of National vs. Local Emission Reduction on PM2.5 in the West Midlands, UK Using WRF-CMAQ”

Conclusion

The climate and environment fundamental has a strong relationship with our living standards in various ways, including our health and our economy. It is clear from the evidence above that actions which benefit the environment are far from mutually exclusive with those that improve our economy – in fact mitigating the risks of climate change can not only prevent costs, it often leads us to achieve outcomes more efficiently, generating more value to our economy.

We’re often inclined to focus on carbon emissions when discussing this area, and whilst this important, there are many other aspects that play a significant role. Energy usage has achieved an increased focus since the energy crisis began in 2021, and whilst support from the government alleviated a large amount of the extra cost, we can continue to bring energy costs down by increasing the energy efficiency of our housing stock. The West Midlands has the highest level of fuel poverty of any combined authority in England, making this of even higher importance to our residents. Another important area that we can influence is increasing the prevalence of green spaces in our region. Alongside the environmental benefits of increased drainage and carbon capture, this also has tangible health benefits for our communities. Air pollution presents another overlap with health, requiring us to consider how we consume fuel both domestically and through transport.

Inclusive Economy

Headline Outcome

An inclusive economy is one where everyone has a stake and is fully included in the process of growing a flourishing and sustainable economy, instead of one where a small number of people benefit first, and then wealth is redistributed later or trickled down. This means that our residents should have secure jobs that pay them a living wage and that everyone should be able to reap the financial benefits of economic growth, regardless of their background.

Productivity

Traditional Measures

Traditional economic measures in the UK often focus on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross Value Added (GVA), often used as a proxy for productivity. The WMCA estimates that the West Midlands region will see an annual GVA increase of approximately 1.3% between 2022-2030, less than the average of 1.5% for the UK.[1] This is valuable as it represents the growth in economic output in the region, relative to the rest of the country. It is important to use this measure with caution and an understanding of its limitations, including that growth in GVA has to be countered against price inflation.[2] GVA also only captures economic activity involving financial transactions, meaning that voluntary or unpaid work, including caring responsibilities, are not reflected in the figures. Due to differences in tax and prices between regions, it should not be used as a comparison of the standard of living between different areas.

Further Measures and Research

There is commonly a focus on maximising GDP when discussing macroeconomic topics, with the belief that a growing economy is inherently a healthy one and vice versa, regardless of the source of growth. Unfortunately, all growth is not equal, with variables including geographic location and personal characteristics significantly impacting the level of benefits a person receives from economic growth. Research on changes in the British economy between 2000-2008 found little evidence that economic growth reduced poverty.[3] It was also found that economic growth increased the wages of top earners but not those below the median. Between 2008-2022 the gap between top earners and the median continued to increase at a slightly slower rate, but the gap between the median and low earners reduced considerably, meaning that whilst overall inequality fell during this period, top earners continued to pull away from the rest.[4] A recent report estimates that the deficit in equality between the UK and 23 comparable OECD countries costs the country approximately £106.2bn every year as of 2023, even when only accounting for the impact on health and crime.[5] If the cost to all services was accounted for, this figure would likely be far larger. This means that reducing inequality is not only intrinsically beneficial, but it would also significantly improve the wider economy. Research in America investigated the impacts of eliminating wealth inequalities, with outcomes including increased consumer spending and expanded economic participation, which not only improves lives but also provides increased economic stability.[6]

As GVA only includes paid work done by residents, inequalities in employment in the WMCA area result in reduced GVA. Women are more likely to be economically inactive, and this inequality with men resulted in a loss of around 8.35% of GVA in 2023, more than in any local economy outside of London.[7] A key driver of this inequality is motherhood, with the high cost of childcare in the UK making full time employment economically unviable for many.[8] Better childcare provision would make it possible for mothers to work more, increasing GVA.

Income, Wages and Employment

Traditional Measures

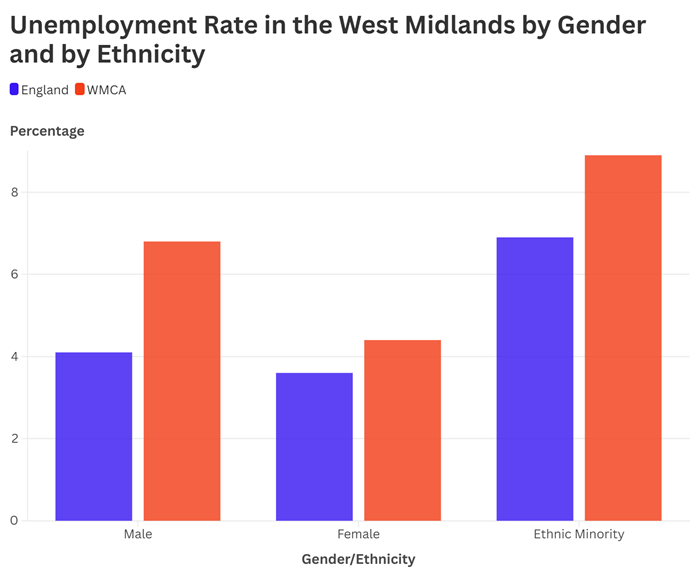

Whilst women were more likely to be economically inactive, only 4.4% of women were classed as unemployed compared to 6.8% of men in the WMCA area in March 2024.[9] Our residents are more likely to be unemployed than any other combined authority in England, with an unemployment rate of 5.7% compared to 3.9% for England. The ethnic minority unemployment rate was at 8.9%, 3.2pp more than the average for all employees in the WMCA area of 5.7%. This highlights a lack of opportunities for residents in the WMCA area and shows that the employment disparity between white British residents and ethnic minorities persists.

[1] West Midlands Combined Authority, “West Midlands Plan for Growth: Scale of the Economic Challenge”

[2] City-REDI, University of Birmingham, “What Is Gross Value Added (GVA)?”

[3] Lee, Neil, and Paul Sissons, “Inclusive Growth? The Relationship Between Economic Growth and Poverty in British Cities”

[4] Financial Times, “Inequality Hasn’t Risen. Here’s Why It Feels Like It Has.”

[5] The Equality Trust, “Cost of Inequality 2023”

[6] Dua et al., “The Case for Inclusive Growth”

[7] Millthorne et al., “Women’s Work: A Local Perspective on Gender Inequality”

[8] PwC, “Women in Work Index 2023”

[9] Office for National Statistics, “Annual Population Survey”

Figure 5: A grouped bar chart comparing the unemployment rate in the WMCA for males, females and ethnic minorities, with the WMCA rate higher in each category

Within the WMCA area, 30.5% of economically inactive residents were classed as on long term sick in the year to March 2024, above the national average of 26.3%.[1] Between 2019-2024 the University of Birmingham estimated that sickness related inactivity rose by 9.8pp, much more than the national average of 6pp.[2] This is a complicated issue but it is clear that more integration between health and employment policies is essential to support residents with health issues and disabilities back into work.

Further Measures and research

Out of the WMCA area workforce, women were much more likely than men to work part time, with 33.3% of women compared to 11.7% of men in the year to March 2024.[3] Both of these proportions were slightly less than the national average at 36% and 12% respectively. In the UK, Women working part time were less likely to want a full time job than men, highlighting the importance of this option for women.[4] 5% of UK employees held a temporary contract in Q1 of 2024, with 21.2% of this group reporting that they could not find a permanent job. Improved support for those on temporary contracts to help them find permanent employment would reduce their risk of becoming unemployed.

For young adults entering the workforce, unemployment can have more of a scarring effect than it does for older people. Research in the UK has found that each month of unemployment between the ages of 18 and 20 results in an average permanent income loss of 1.2% per year but by the time workers reach 24 this impact disappears.[5] In the year to March 2024, 16.3% of those aged 16-24 in the WMCA area were unemployed, a similar level to Greater Manchester but considerably more than the national average of 11.8%. People in this age group should be a priority for targeted support to find employment to minimise the impact on their future employment opportunities and earnings.

Increased educational attainment has significantly contributed to growth in productivity in the UK.[6] Analysis from the DfE has found that training has a sizable and significant effect on labour productivity, particularly in industries with a greater proportion of highly qualified workers. To ensure that productivity growth is strong in the West Midlands, it is important that businesses are incentivised to invest in training their employees. Approximately 22.1% of residents in the region aged 16-64 were economically inactive in 2024, reducing the number of employees and skills available to businesses which reduces productivity.[7]

[1] Local Government Association, “Percentage of the Working Age Population by Employment Status”

[2] City-REDI, “Uneven Rise in Economic Inactivity: A Growing Concern for the West Midlands”

[3] Office for National Statistics, “Annual Population Survey”

[4] Office for National Statistics, “Full-Time, Part-Time and Temporary Workers, Seasonally Adjusted (EMP01 SA)”

[5] De Fraja, Lemos, and Rockey, “The Wounds That Do Not Heal: The Lifetime Scar of Youth Unemployment”

[6] UK Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, “UK Skills and Productivity in an International Context”

[7] City-REDI, University of Birmingham, “West Midlands Economic Impact Monitor – 30 May 2024”

Business Resilience

Traditional Measures

Steady rates of business birth and survival are an important part of a healthy economy, creating new employment opportunities for residents.[1] Business birth rates fell in England between 2021-2023 by around 13%, but they’ve fallen in the West Midlands region by 23%.[2] Despite the sharper decline in business birth rates between 2021-2023, the birth rate in the West Midlands had grown at an above average speed between 2018-2021, meaning that the proportion of English businesses being born in the region only fell from 9.5% to 9.3%. Businesses created in 2018 had the worst 5-year survival rate of any region in the UK in the West Midlands at 34.7%.

Further Measures and Research

Declining business birth and survival rates stifle productivity growth, harming the local economy.[3] The regional strategic economic plan highlights the importance of improving the skills base within our region to ensure that businesses have access to skills they require. In 2022, employers in the region struggled to fill 35% of vacancies due to a lack of skills amongst applicants.[4] This is clearly an important topic for employers and so upskilling our region’s workforce must be a priority to stimulate economic growth.

Conclusion

The health of our economy is often reported using traditional measures such as GDP, with government missions often built around ensuring positive growth. When discussing productivity, GVA is often used to track fluctuations in the value of paid labour. Economic growth is very complex, and these measures are relatively straightforward and consistent, making them an accessible starting point.

Beyond this, we must understand what GDP and GVA do not measure and be careful not to draw inaccurate conclusions through misapplying them. Whilst growth in GDP equates to increased value of goods and services in the economy, it does not tell us who is benefitting from it.

[1] Office for National Statistics, “Business Dynamism in the UK Economy: Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 1999 to Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2019”

[2] Office for National Statistics, “Business Demography, UK”

[3] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Strategic Economic Plan: Full SEP Document”

[4] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Employment and Skills Strategy 2024–2027”

Power and Participation

Introduction

Power and participation are about the extent to which people and have a voice in influencing the things that matter to them. People who feel that they have choice and control over their own personal circumstances, and who feel that they have power to participate and shape the places in which they live and work, will feel a greater sense of belonging and a greater share in the prospects of a place.

Agency and Power

Traditional Measures

Participation by residents can take on many forms, including more traditional forms such as voting in elections and referendums, engaging with elected officials, volunteering in the community and more, along with alternative forms such as attending protests and signing petitions. Of these activities, voting in elections is a traditional measure of the population’s engagement and power to voice their opinion on how decisions that impact them are made. There has been considerable research into what influences election turnout, with a range of factors proposed, including a sense of civic duty, levels of political engagement, and the perceived importance of the outcome.[1] In the 2024 general election, 57.3% of eligible voters in the West Midlands region submitted a ballot, slightly below the national average of 59.7%.[2] Out of the 11 regions of the UK, the West Midlands had the median turnout, with the lowest turnouts in the north of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. At a national level, this represented a fall of around 7.6pp from the 2019 general election, with the fall in the West Midlands slightly higher at 7.8pp.

Further Measures and Research

In the West Midlands region, there are 57 parliamentary constituencies, which 365 candidates contested in the 2024 general election.[3] This means there were an average of 6.4 candidates per seat, less than the average of 6.9 for England, meaning residents in the region had less choice. Turnout fell across the country in 2001 to 59.4%, and despite increases in turnout up to the 2017 election, it fell to only 0.3pp above the 2001 level in 2024.[4] This is still much higher than in elections for local government, with the 2024 mayoral election in the WMCA area seeing a turnout of 29.8%, almost half of the general election turnout for the West Midlands region in the same year.[5] Even the largest turnout at a local election in the WMCA area in 2023, 30.1% in Solihull, falls far short of the 57.3% at the general election.[6]

Influence and Civic Engagement

Traditional Measures

Data from the Community Life Survey by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) shows that people don’t feel they can personally influence decisions affecting their local area, with only 23% of those surveyed in England in 2023/24 feeling that they can.[7] In the WMCA area, this is slightly higher, with 25% feeling that they can personally influence decisions, but this still represents a minority of residents. This does not seem to be an area of concern for the majority of residents though, as only 29% agreed that they would like to be more involved in decisions made by their council in the WMCA area. Fewer residents in the WMCA area reported any civic participation in the previous 12 months, 29%, than the average for England of 33%. The community life survey defines this as engagement in democratic processes, including contacting a local official, signing a petition or attending a public rally.

[1] UK Parliament POST, “Election Turnout: Why Do Some People Not Vote?”; Stockemer, “What Affects Voter Turnout? A Review Article/Meta-Analysis of Aggregate Research”

[2] House of Commons Library, “2024 General Election: Turnout”; Uberoi and Johnston, “Political disengagement in the UK: Who is disengaged?”

[3] House of Commons Library, “Who Stood in the 2024 General Election?”

[4] House of Commons Library, “2024 General Election: Turnout”

[5] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Election Results”

[6] Local Government Association, “Local Election Turnout”

[7] Department for Culture, Media and Sport, “Community Life Survey 2023/24 Annual Publication”

Figure 6: A bar chart comparing the percentage of residents who took part in any volunteering in England, the West Midlands region, and the WMCA in the previous 12 months in 2023/24, with the lowest percentage in the WMCA

Residents can influence their local communities without directly engaging with their council or government. One common form of this is volunteering. The community life survey found that approximately 51% of residents in the WMCA area took part in some form of volunteering within the previous 12 months when asked between October 2023 and March 2024, slightly below the national average of 54%.[1] Research has found that volunteers report higher levels of community identification and social support.[2] This suggests that increased levels of volunteering can improve social cohesion. As only 28% of residents in the WMCA area reported that they trust many of their neighbours, far below the English average of 41%, this is clearly a challenge for our communities.[3] There is also a strong association between volunteering and increased levels of wellbeing and life satisfaction, showing that the benefits extend beyond community participation.[4] It should be a priority to make it easier for people to get involved in volunteering in their community as this can build both participation and improve individual wellbeing.

[1] Department for Culture, Media and Sport, “Community Life Survey 2023/24 Annual Publication”

[2] Bowe et al., “A Social Cure in the Community: A Mixed‐Method Exploration of the Role of Social Identity in the Experiences and Well‐Being of Community Volunteers”

[3] Department for Culture, Media and Sport, “Community Life Survey 2023/24 Annual Publication”

[4] Jenkinson et al., “Is Volunteering a Public Health Intervention? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Health and Survival of Volunteers”

Figure 7: A bar chart comparing the percentage of residents who felt that many of their neighbours could be trusted by area in England, the West Midlands region, and the WMCA in the previous 12 months in 2023/24, with the lowest percentage in the WMCA

Further Measures and Research

A report from the House of Lords highlighted that elections are only one method of participating in democracy and that active citizens should not only be involved in selecting their government but also in how they are governed.[1] Dr Henry Tam, a lecturer at the University of Cambridge and expert on democratic participation, told a House of Lords committee that there is insufficient democratic participation in the UK, and that citizens engage using methods such as protesting but that they do not engage with governing bodies or political institutions.[2] In addition to protests, starting and signing petitions has been a common form of engagement, with the UK Parliament launching a petition service in 2015. Although many of these petitions are ultimately rejected, some have brought about change and this form of engagement serves an important role in a society where many are now digitally engaged.[3]

Whilst residents can choose to engage in democratic processes in their area, there is also an onus on public officials to proactively engage members of the local community. This is most effective when used as a long term tool embedded in the democratic process, rather than for singular legislative issues.[4] An example of this from the WMCA included engaging members of the public through the Greener Together Citizens' Panel which sought to bring together residents to provide their views on how we can approach a variety of issues related to the environment and achieving net zero emissions.[5] The members of the panel were selected with the intention of forming a group that was reflective of the region’s population with regard to a range of characteristics. This helps us to understand the views of a diverse range of communities as well as strengthening the links between them and local government.[6] Co-production of policy and programmes with local residents doesn’t only build better links with the community and increase participation, it also improves the services provided by local government.[7]

[1] House of Lords Select Committee on Citizenship and Civic Engagement, “Chapter 6: Democratic Engagement – Improving Connectivity”

[2] House of Lords Citizenship and Civic Engagement Committee, “Oral Evidence: Local Communities”

[3] Leston-Bandeira, "Parliamentary petitions and public engagement: an empirical analysis of the role of e-petitions"

[4] Chwalisz, “Citizen Engagement in Politics and Policymaking: Lessons from the UK”

[5] West Midlands Combined Authority, “West Midlands Greener Together Citizens’ Panel 2022–2024”

[6] Khan et al., “Diversity, Community Engagement and Co-Design in Research: A Rapid Review”

[7] Vanleene, Verschuere, and Voets, “Benefits and Risks of Co-Production: A Preliminary Literature Review”

Trust

Traditional Measures

Recent national surveys consistently find that public trust in the government is low, although the level of trust in local government is slightly higher than national government.[1] The ONS reported that 34% of people had high or moderately high trust in local government in the UK in 2023, 7pp more than the 27% who said this about the UK Government. A survey from the LGA in 2021/22 found a more pronounced difference, with only 16% of residents in the West Midlands region reporting that they trust the national government to make decisions about services in their local area, whilst 71% would trust their local council.[2] More research is needed to truly understand why residents feel this way.

Further Measures and Research

Developing relationships with underserved communities engages those communities in the democratic process and increases their trust in government. Measuring the trust of constituents in their government is a constant challenge as there are a lack of traditional measures that truly capture it. Trust is a complex intangible state of the relationship between authority and citizens, and so researchers often rely on surveys to gauge the opinions of the public.[3] Unfortunately, these sample sizes are often relatively small and so it can be challenging to understand how trust varies across different regions and communities in Britain.

Conclusion

Due to the nature of its scope, power and participation is an area with less traditional quantifiable measures, outside of election turnouts. Topics such as how engaged members of a community are and how empowered they feel to make change in their local area are very subjective, making it challenging to use rigorous methods. As a result, qualitative research methods such as surveys, interviews and case studies are more prevalent in this area as they allow us to collect rich data on our residents’ views.

Whilst election turnout tells us the proportion of residents exercising their democratic right to decide who governs them, this is only one method of participation. Residents have access to elected officials and can influence their work through various means, including direct correspondence, signing petitions, and engaging in protests. Beyond engaging with the political system, volunteering allows us to have a direct influence in our local area.

In local government, we can also empower our residents by providing them the opportunity to influence our work. Co-production can improve the work we do by incorporating the views and priorities of our residents, which can inform how we design interventions, resulting in more effective outcomes.

[1] Office for National Statistics, “Trust in Government, UK: 2023”; Local Government Information Unit, "The Core Principles of Trust Applied to Local Government"

[2] Local Government Association, “Regional Polling Results”

[3] Hansen, “How Government Efficiency Shapes Political Trust: Evidence from the Case of Brexit”

Affordable and Safe Places

Introduction

Affordable and safe places is about everyone having decent homes that they can afford, neighbourhoods where they feel secure, and feel a sense of belonging in the place that they live. When people’s housing and neighbourhoods don’t meet their needs, this can have a serious impact on their health and wellbeing and can limit the future prospects of children growing up in these environments.

Decent Homes For All

Traditional Measures

The UK Government provides a range of requirements for a dwelling to be considered decent, including that it meets the current statutory minimum standard for housing, is in a reasonable state of repair, has reasonably modern facilities and provides a reasonable degree of thermal comfort.[1] In the West Midlands region in 2023, around 16.1% of homes of all tenures were considered non-decent, one of the highest regional rates in the U.K.[2] Privately rented homes were most likely to not meet the standard, with 25.4% of homes considered non-decent, Local authority and housing association were least likely to be non-decent in the region. Other factors also determined who was more likely to live in a non-decent home, with some groups disproportionately impacted. These groups included, Black residents, those with an income in the lowest quintile, those living in poverty and single occupants aged under 60.[3]

[1] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, “A Decent Home: Definition and Guidance”

[2] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, “English Housing Survey 2023 to 2024: Headline Findings on Housing Quality and Energy Efficiency”

[3] Health Foundation, “Inequalities Between Groups of People Living in Non-Decent Homes.”

Figure 8: A grouped bar chart comparing the percentage of homes that are non-decent by tenure in England and the West Midlands region in 2023/24, with the West Midlands reporting lower levels for local authority and social housing

Further Measures and Research

Whilst not considered when assessing if a home is decent, 7.8% of homes were considered overcrowded in the WMCA area in 2021, 1.4pp more than the English average.[1] Living in an overcrowded home is associated with worse levels of mental health.[2] A report by the National Housing Federation found that around half of children living in overcrowded homes struggle to do their homework because of a lack of space.[3] They also found that ethnic minorities were three times as likely to be affected by overcrowding. In 2022-23 there were 1.5 million children in England living in homes that did not meet the decency standard, with around 1 million children living in hazardous houses and nearly 800,000 living with damp.[4] The median cost per household to rectify these issues and make these dwellings decent in the West Midlands region in 2022 was estimated to be £6,408, the lowest in England.

Disposable Income

Traditional Measures

The 17.9% rate of fuel poverty in the WMCA area in 2023 was considerably higher than the rate of 11.4% in England..[5] By comparison, Greater Manchester had a fuel poverty rate of 11.9%, 7pp less than the WMCA area.

Further Measures and Research

Damp in a child’s bedroom is associated with increased respiratory problems, highlighting the impact that inadequate homes can have on health.[6] Incidences of damp in homes could be exacerbated by behaviours related to fuel poverty. Fuel poverty in England is measured using the Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) indicator. This is defined as living in a property with a fuel poverty energy efficiency rating of band D or below and where spending the required amount to heat the home leaves an income below the poverty line.[7] Where residents are living in fuel poverty, they are likely to avoid turning on their heating as often as they should to save money to cover their other needs.[8] This increases the risk of mould developing and contaminating their home, making it unsafe and non-decent.[9] This is an example of additional costs and health determinants being accumulated due to being poor. Research has shown that there is a relationship between fuel poverty and self-assessed health, highlighting the importance of addressing fuel poverty to improve health outcomes.[10] This represents a hazard and a health risk to residents in these homes.

Prevention of Homelessness

Homelessness is the ultimate exclusion for citizens and has far-reaching consequences for those affected and for local communities. It can affect anyone, but some people are more at risk than others. Homelessness is legally defined as having no home available anywhere and that can be reasonably occupied.[11] Homelessness manifests in many ways and is not solely about the people sleeping rough, this visible form of homelessness is just the tip of the iceberg.[12] The reality of homelessness is much broader and there are many hidden forms of homelessness that are harder to see and measure including ‘homelessness at home’, squatting, living in temporary accommodation, and sofa surfing.

Traditional Measures

In 2023/24, 17,310 households were assessed as being owed a homelessness duty in the WMCA area.[13] 57% of those owed a duty were non-white, despite only 39% of the population being non-white. In particular Black British, Caribbean or African applicants made up a significantly large proportion of those owed a duty at 18%, despite only making up 8% of the population.[14]

At the end of March 2024, there were 6,520 households in the WMCA area (there was no data for Wolverhampton) living in temporary accommodation, of these, 5,537 households included children.[15] There were 983 single occupant households. Many of these households comprise of single women living with dependent children. Single women living in these circumstances experience extremely challenging financial conditions, as they struggle to work due to their caring responsibilities.[16] These women are particularly vulnerable as a result, and the living conditions and experiences of this group are an important consideration for policymakers in this area.

Local authority and housing association stock cannot meet the needs of homeless residents, with only 40% of those living in temporary accommodation in this type of accommodation in the WMCA. 42% of these residents live in bed and breakfast hotels (B&Bs), nightly paid accommodation, hostels or authority leased private sector accommodation. The costs to the authority for these types of accommodation are high, and the living standards in B&Bs and hostels are often very poor.[17]

Further Measures and Research

The proportion of people in the UK experiencing homelessness is much larger than in comparable countries, although definitions of homelessness vary.[18] In England, rough sleeping is defined as sleeping, about to bed down or bedded down in the open air, or sleeping in buildings not designed for habitation.[19] For this group of people, health related outcomes are poor, with analysis of hospital admission records finding that the median age of death for people who sleep rough was 20 years younger than those admitted to hospital who were not rough sleeping but living in the most deprived quintile.[20] Rough sleepers were also much more likely to suffer from chronic health conditions such as asthma and COPD than those who are housed.[21] Preventing homelessness by identifying and addressing the different barriers faced by our diverse communities and helping to enhance people’s protective factors so that homelessness can be prevented wherever possible is not only morally desirable, it would also save a significant amount of public money. In 2012, the Government estimated that homelessness in England costs around £1bn per year but this figure is likely much higher now due to the large increase in homelessness figures since then.[22] Shelter reported that local councils had spent £2.3bn just on providing temporary accommodation in 2023/24.[23] Whilst the ratio of residence-based earnings to house prices of 7.1 in the West Midlands region was less than the average for England of 8 in 2023, it is still a sharp rise on the ratio of 5.72 in 2013.[24] Houses becoming less affordable is a key driver of homelessness, meaning that policymakers must work to ensure there is a sufficient supply of affordable housing.[25]

Community Safety

It is crucial that we not only provide safe, affordable and decent homes for our residents to live in, but that we also ensure that the neighbourhood around them is a safe place and that residents feel safe regardless of personal characteristics.

Traditional Measures

Unfortunately, the more deprived you are in England, the more likely you are to live in a high-crime neighbourhood.[26] Data provided by West Midlands Police shows higher levels of crime in the WMCA area between May 2020 and December 2024.[27] Within this time period, violent crime, shoplifting, possession of weapons and public order offences have all seen a rise. Anti-social behaviour has continued to fall, with 1,992 offences in December 2024, down from 8,340 in December 2010. This could be a sign of a reduction of disturbances in local neighbourhoods, but this decrease could instead reflect a decrease in reporting.

Further Measures and Research

There is a strong link between high levels of neighbourhood crime and mental health conditions including depression amongst residents.[28] Research also shows that when residents feel safe in their communities, they tend to walk more often.[29] This is good for their health and for the environment, reducing emissions generated from journeys that may otherwise have relied on cars. The community life survey found that 62% of residents in the WMCA area were satisfied with their local area as a place to live between January and March 2024, 12pp less than the average in England.[30] Qualitative research aimed at understanding why residents feel this way would help us to prioritise improvements to address this.

Conclusion

A common theme amongst the measures and research for this fundamental is that residents with lower incomes in more deprived areas endure worse living conditions. This was the case for non-decent housing, overcrowding, and fuel poverty. These challenges often present further barriers to living a good quality of life because of poorer health, extra costs, and poorer educational outcomes for young people.

Residents who can’t make ends meet are then faced with the prospect of homelessness. This outcome reflects significant ethnic inequality, with Black British, Caribbean or African residents making up a disproportionately large amount of those applying for relief. A significant number of families living in temporary accommodation are single female parent led. The women living in these situations are vulnerable, but local authorities are so overwhelmed by the scale of this challenge that they cannot meet their needs. Local Councils spent an estimated £2.3bn just on providing temporary accommodation in 2023/24, demonstrating the high cost of this issue.

Building safe communities in our region is not only important for the wellbeing of residents, but also for improving mental health and creating an environment where people feel safe to walk more. Residents in the WMCA area were considerably less likely to report being satisfied with their local area than the national average.

[1] Local Government Association, “Overcrowding”

[2] Health Foundation, “Relationship Between Living in Overcrowded Homes and Mental Health”

[3] National Housing Federation, “Overcrowding in England 2023”

[4] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, “English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023: Housing Quality and Condition”

[5] Department for Energy Security & Net Zero, “Sub-regional Fuel Poverty in England, 2025 Report (2023 Data)”

[6] Ruffles, et al., “Visible Damp in a Child’s Bedroom Is Associated with Increased Respiratory Morbidity in Early Life: A Multicentre Cohort Study”

[7] UK Government, “Fuel Poverty Statistics”

[8] Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, “Research into the Behaviours and Attitudes of the Fuel Poor in England”

[9] Sharpe, Thornton, Nikolaou, and Osborne, “Fuel Poverty Increases Risk of Mould Contamination, Regardless of Adult Risk Perception & Ventilation in Social Housing Properties”

[10] Kahouli, “An Economic Approach to the Study of the Relationship between Housing Hazards and Health: The Case of Residential Fuel Poverty in France”

[11] Public Health England, “Homelessness: Applying All Our Health”

[12] West Midlands Combined Authority, “Designing Out Homelessness: Briefing Paper”

[13] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, “Statutory Homelessness in England: Financial Year 2023–24”