The six components of our Growth Plan

Building on our West Midlands Theory of Growth, we are proposing to divide our Growth Plan into six component parts. Three of these focus on the vital role that businesses play in driving growth. A fourth considers our place-based approach and the fifth our people and skills. Our final component concerns the region’s institutions and the story that we tell about the West Midlands economy.

1) High Growth Clusters and Innovation

The West Midlands has a number of business clusters that are at the vanguard of our drive for growth, and 6 universities delivering multiple areas of internationally recognised research that have tangible impacts beyond academia. For over two centuries, the global economy has been shaped by technologies born in the West Midlands and still today we have businesses that are global leaders in the products and services that will define 21st century economic success. While national industrial strategy remains focused on growth ‘sectors’, in the West Midlands many of our global strengths sit at the interface between traditional industrial sectors like manufacturing and logistics and emerging new technologies and tradable services.

Through detailed analysis, the West Midlands Plan for Growth, first published in December 2022, identified eight primary economic clusters where the region could ignite above-forecast levels of growth. These are clusters where the West Midlands has comparative advantage and businesses are confident to invest. Plan for Growth also identified a small number of disruptive, nascent clusters—like Very Light Rail and 5G adoption. Together, these business clusters represent between 12% and 15% of the regional economy, but their potential impact is huge.

In October 2024, government published Invest 2035—its industrial strategy green paper—with a clear goal of boosting domestic and international business investment. A key element of the government’s approach is to unlock regional growth and build upon the sector strengths found in different places. In support of the National Industrial Strategy, and building upon the analysis behind Plan for Growth, the West Midlands has put forward 5 regional growth-driving sectors and clusters which will bring focus to our emerging Growth Plan. These are set out in the table below.

| Priority | Growth Potential | Key market strengths, assets and investment opportunities |

| Advanced engineering, light electric vehicles and batteries | Modest output growth and potential reduction in jobs but will contribute to very large productivity increases. Critical for economic resilience and transition. |

|

| CleanTech with a focus on smart energy systems | Strong output growth, with commensurate additional jobs across scientific and technical roles. Important wider benefits such as decarbonisation and energy security. |

|

| Health and medical devices, diagnostics and associated digital healthcare | Significant output and jobs growth and moderate productivity growth across scientific and technical suppliers. Important spillover opportunities to associated industries |

|

| Digital, tech and creative | Very significant growth potential, with strong jobs and productivity growth. |

|

| Modern professional and financial services | Modest growth and jobs potential: impact of technology creating opportunities for productivity gains, new services and markets but with potential counter muting of jobs from ensuing shift in workplace composition. |

|

Innovation is the driving force underpinning all of our cluster potential and the West Midlands has a very strong pedigree in this area, not least in applied research—turning bright ideas into tangible goods and services. Over the past 2 years, the West Midlands has pioneered both the national Innovation Accelerator and Made Smarter programmes creating or upskilling over 5,000 jobs in high productivity businesses. The WM5G programme has helped to make the West Midlands the best-connected region outside London. And last November, the West Midlands was named as one of the top three city-regions in the prestigious European Capital of Innovation awards.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in the West Midlands

The West Midlands also has burgeoning AI strengths. The wider region is home to 300 AI companies representing 10% of the national total. It has strong academic research capabilities, with universities like University of Birmingham (a member of the Alan Turing Institute), Coventry, Aston, and Wolverhampton each with their own particular specialisms. The region also benefits from high performing data centres such as nLighten and is exploring the creation of distributed AI compute ecosystem though its AI Growth Zone partnership. To further leverage AI, the WMCA has undertaken pioneered an AI Accelerator Programme and is now developing an AI Adoption Blueprint.

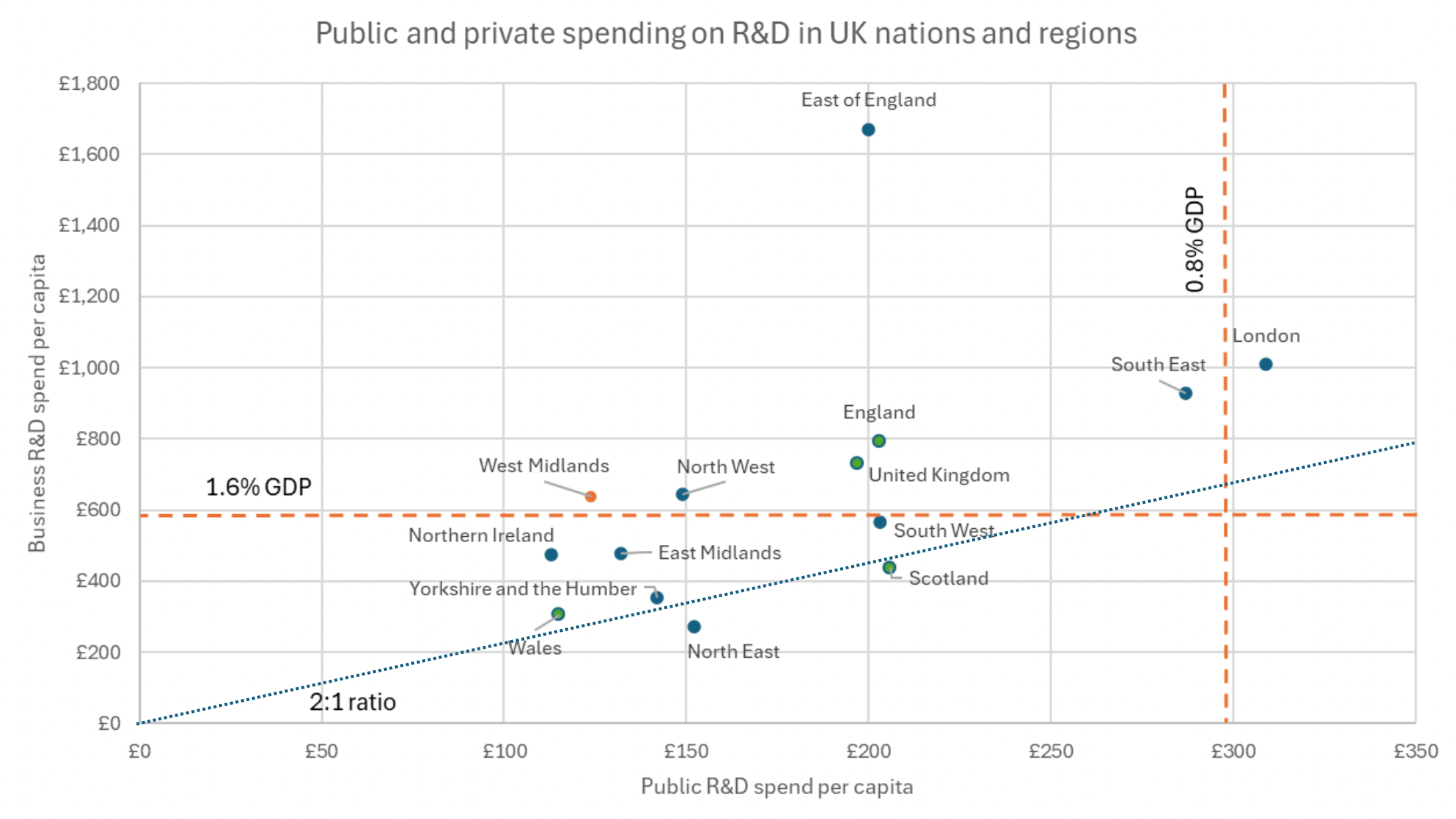

But while last year the region leveraged over £3bn in private sector investment in R&D, government research funding is not keeping pace. The West Midlands has the second- lowest public-private R&D spending ratio in the UK and R&D spending in the region tends to be concentrated in key sectors; and very specialised in just a few firms. The region also has significant issues with technology adoption ranking poorly in Tech UK’s Local Digital Index. An increase in government R&D expenditure—especially in translational research and adoption across a wider spectrum of technologies—is critical to raising regional productivity. In the 2021 Research Excellence Framework, all 6 universities in the West Midlands in receipt of innovation funding are delivering multiple areas of internationally recognised research that has tangible impact beyond academia.

Figure 3: Scatter chart showing public and private spending on R&D in UK nations and regions

And our business composition has untapped potential. The evidence suggests the UK—and West Midlands in particular—lacks major Tier 1 suppliers (direct suppliers to an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM)) in major traded clusters. This is important because Tier 1 suppliers often provide components with high added-value and have close relationships with OEMs to assist with research, development and new management practices.

Outcomes

Over the coming ten years we will prioritise our collective efforts to increase the rate and level of R&D adoption by businesses, focused on the West Midlands’ high growth cluster strengths and translational research.

Questions

3) Do you agree with our identification of the West Midland’s key cluster strengths and what needs to be done to support and develop them?

4) How can the West Midlands build on its innovation strengths and increase government investment in R&D?

2) Business Leadership and Investment

Boosting our high growth clusters is critical to driving regional productivity growth, but those businesses at the vanguard of growth represent just 12-15% of the economy and so they alone will not turn the tide. Over the last 20 years, academics from LSE and Cornell universities have used a World Management Survey to evidence a strong association between management practices, firm-level productivity, profitability, business valuations and firm survival. Improving regional productivity means improving business leadership, where the ONS finds the wider West Midlands region scores lowest for business management. Research by City-REDI shows that an important part of the regional productivity problem is that West Midlands firms have lower productivity, even in comparison to their peers in other regions.

This points to two problems.

First, it suggests that we might have an issue with business leadership and management. While this matter deserves more investigation, it seems business leaders seem somehow less able to invest in activities that might drive their productivity; one explanation could be the large number of Tier 3, 4 and 5 firms have less autonomy and prioritise efficiency of operating to low margins rather than being growth orientated. At a broader level, the Productivity Institute found a weakness in management competencies accounted for 30% of the difference in productivity between the Midlands and international benchmarks.

Second, aside from R&D, the West Midlands seems to suffer from low levels of business investment in the region more generally. Recent research by the Harvard Kennedy School for Business and Government has shown that the West Midlands scores badly for the number of investment deals and the quantum of investment in both high-growth firms and SMEs in comparison with other regions.

It is very likely that these two problems are related. The lack of access to finance and business investment to drive innovation and growth, may well be a function of the fact that business leaders may not be demanding it. Once again, the reasons for this may be complex but nonetheless they need to be addressed.

When it comes to investment, the tide may now be turning, particularly with respect to foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2023, the EY Attractiveness Survey found that Birmingham is the second best-performing UK city for FDI outside of London; and the West Midlands the 7th best in Europe. This represents a strong platform for further investment, galvanised by the West Midlands to be the first region to have an International Strategy co- designed by a range of civic institutions, Chambers of Commerce, universities, sporting and cultural institutions and the Department for Business and Trade.

The West Midlands International Strategy

The West Midlands International Strategy outlines a comprehensive plan to enhance the region's global presence and economic performance. The strategy leverages the region's strengths, including its SME exporting base, world-class universities, and cultural assets, to increase trade, investment, innovation, and visitor numbers. By 2030, the West Midlands aims to be recognised as a leading destination for trade, investment, and tourism.

The strategy proposes the formation of the Global West Midlands (GWM) Partnership to enhance coordination of international activities, maximise competitive advantages and align regional and national government activity. This approach is crucial given the volatile global environment and the need for a productive, innovative economy. The strategy emphasises the importance of transitioning to a net-zero carbon economy and addressing resource constraints.

Key pillars of the strategy include trade, investment, innovation, and the visitor economy. The strategy identifies primary markets such as the United States, Europe, China, India, and the UAE, as well as developing markets like Australia/New Zealand, Canada, and South East Asia. The GWM Partnership will oversee the implementation of the strategy, ensuring coordination and alignment of activities to achieve maximum impact. Attracting greater levels of domestic and international business investment will be the key to future growth.

Outcomes

Over the coming ten years we will prioritise our collective efforts to:

- Transform the standards of business leadership and management across the region, including to support the adoption of technology.

- Maintain the West Midlands’ standing as the top region for FDI investment outside of London.

Questions

5) What could be done to strengthen business leadership and management in the West Midlands and what support does business need to invest in success?

6) How do we sustain our growing reputation for foreign direct investment?

3) Our Everyday Economy

The large majority of our people and businesses in the West Midlands operate in what might be called the ‘everyday economy’: those labour-intensive, non-tradable activities mostly serving very local markets. These include health, education, social care, public administration, retail, hospitality, leisure, arts, tourism, construction, utilities, transport, and food production.

In the West Midlands, a recent study has shown that everyday economy jobs make up 63% of all jobs in our region. These jobs are often found in areas of high deprivation and are characterised by younger, more diverse, and often female, disabled, or foreign-born workers. They tend to have poor job quality, including low pay, insecure work and while AI may replace some of these jobs, it is expected they are more likely to be augmented by AI rather than replaced.

While opportunities to drive up productivity in such jobs might be more limited, it is essential that our West Midlands Growth Plan attends to this part of our economy too. Normally, businesses in the everyday economy take what could be termed a ‘low road’ approach to productivity: seeking ever greater efficiencies in labour costs by bearing down on wages and time management. Our recent study has identified a number of ‘high road’ approaches that have been adopted by certain firms and public authorities. These include commitments to a Real Living Wage; improving job quality and staff retention through better training and scheduling; and allowing staff to play a greater role in designing productivity improvements.

There are also policy levers available to help shape the development of the everyday economy in the West Midlands:

- At a national level, government could set higher minimum standards and regulations such as those proposed in the forthcoming Employment Rights Bill.

- The WMCA and its local authorities can also play a role:

o Setting stricter conditions around public procurement, grants and other forms of support;

o Using planning mechanisms to require local employment practices;

o Insourcing services; and

o Developing charters to promote job quality and good practices. - Policy-makers can also help workers in the everyday economy indirectly through skills provision, improving accessibility through transport and supporting housing affordability and quality.

Ultimately though, it is no doubt the case that employers themselves need to make the difficult choices about whether they take the low road or the high road to increasing productivity. It may be that this is best done sector by sector, an approach adopted in countries like Germany and Spain, with support from business representative organisations.

Another vital part of the everyday economy is the social economy: a collective term for social enterprises, cooperatives, mutuals, community-owned businesses, and other not-for- personal-profit organisations that use a trading model to generate funds and tackle inequality.

According to the latest research from the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) the social economy in the West Midlands has:

- Over 9,800 social economy organisations;

- 70% of which are small to micro in size with an average turnover of £42,000 per annum and only 5% exceeding £1 million; and

- 70% of which are run by women and over 50% are by people from racialised communities; with

- 103,000 employees, supported by;

- 250,000 volunteers.

In the West Midlands, work led by the WMCA has started to boost the social economy in the region with those social businesses receiving support increasing trading income by 48% and the creation of 175 new jobs. The development of Social Economy Clusters and networking events has fostered partnerships and leveraged additional funding and support worth around £750,000. National recognition of WMCA’s approach has led to invitations to address major conferences and interest from other combined authorities.

To realise its full potential in addressing inequality and helping achieve inclusive growth, further investment is needed in bespoke business support; overcoming myths and barriers which are preventing some social businesses from taking on repayable finance; and nurturing local clusters to foster collaboration and mutual support.

Once again, the social economy in the West Midlands is recognised nationally as a huge asset, but in the region it rarely finds itself in the limelight.

Outcomes

Over the coming ten years we will prioritise our collective efforts to:

- Improve job quality and pay across the region’s everyday economy.

- Double the size of the social economy with effective social economy clusters in every local authority area.

Questions

7) What needs to be done to create and support better quality jobs?

8) How do we better support the social economy to build its financial sustainability while continuing to deliver social impact?

4) Our Places

Earlier in this chapter we identified the fact that the West Midlands’ economic geography represents a foundational strength and its location and relationship with other parts of the UK makes it a hub for national economic activity. Its strength also lies in its diversity of cities and towns, centred around Birmingham as its core city. Our polycentric geography offers a “goldilocks” combination of scale, resilience and quality of life.

In the following chapter we set out in more detail how we will maximise this place-based approach to economic growth. Over the past year, local authorities have developed Place- Based Strategies, identifying opportunities for investment and development and how places boost the quality of life, including through high street, cultural and major event offerings. The WMCA is forming a strategic relationship with Homes England to focus public investment on major housing projects.

The following chapter also identifies several key development sites and corridors of opportunity that are crucial for the region's growth. These include:

- HS2 Stations: HS2 is one of Europe's largest infrastructure projects and will reduce travel times from the capital to Birmingham and the West Midlands to just under or just over 40 minutes for the HS2 Interchange at Arden Cross and Curzon Street respectively. The Arden Cross development will bring forward 680,000 square meters of commercial development and 2,750 homes, while Curzon Street station at the heart of Birmingham will be a magnet for international investment and drivers of catalytic economic transformation.

- West Midlands Investment Zone: The West Midlands Investment Zone blends a mix of capital investment, tax incentives, and business support programs to generate long-term economic growth in advanced manufacturing, green industries, battery technology, med-tech, and digital. It is anchored by three key sites: the Coventry-Warwick Gigapark focusing on electric vehicles and battery manufacturing, the Birmingham Knowledge Quarter with research and incubation activities in digital technology and med-tech, and the Wolverhampton Green Innovation Corridor driving new growth in green industries.

- Growth Zone Sites: There are three major strategic site clusters that have attracted a similar business rate retention offer: along the Sandwell to Dudley Metro Extension corridor, around J10 of the M6 in Walsall, and in the strategic corridor from East Birmingham to North Solihull. The retention of business rates uplift in these areas can underpin upfront investment through models such as tax increment financing and provide the relevant local authorities with wider reinvestment opportunities to support growth.

- Birmingham City Centre: The city is embarking on a renaissance powered by the alignment of public sector commitments, political alignment at national, regional, and local levels, and private sector investment. HS2’s Curzon Street Station sits immediately beside one of the region’s most successful Enterprise Zones, delivering new commercial spaces that have attracted the likes of Goldman Sachs, Arup, and PWC, and sparking landmark growth in the creative industries in Digbeth. To the north of Curzon Street lies the Birmingham Knowledge Quarter, with an ambition to become a global innovation district in tech-inspired innovation, particularly in medical solutions and advanced manufacturing. Birmingham Sports Quarter represents a £3 billion commitment to bring forward a new stadium and national leisure attraction, creating jobs and skills opportunities in one of the most deprived areas in the country.

Spatial Development Strategy (SDS)

Government has made a commitment to deliver 1.5 million new homes during this Parliament and has already published a revised National Planning Policy Framework which liberalises previous planning policy and reinstates mandatory housing targets. It has also brought forward a Planning and Infrastructure Bill which makes provision for the introduction of Spatial Development Strategies (SDS) to be led by mayoral combined authorities like the WMCA.

The SDS will be a vital complement to the West Midlands Growth Plan. It will be a land-use planning strategy that indicates broad growth locations across the region. The SDS will need to demonstrate how the region will meet the collective housing need, including redistribution where need generated in a local authority cannot be met within that authority’s boundaries. It will include details of the infrastructure necessary to support development, including that for mitigating or adapting to climate change and taking account of the local nature recovery strategy.

It is proposed that the SDS will prioritise bringing brownfield sites into use and increasing housing density. It will provide a positive framework to bring forward the delivery of such sites, coupled with long-term funding to address these challenges. The relationship between the West Midlands Growth Plan and SDS is critical in this regard, just as it is with the Local Transport Plan.

The SDS will also very likely require new arrangements with neighbouring local authorities to meet housing need. This will require a successor mechanism to the Duty to Cooperate or could take the form of a more explicit shortfall mechanism to allow referral from one SDS area to another.

*Outcomes and Questions are set out in Chapter 2 below.

5) Our People and Skills

Many would argue that the true strength of any regional economy is its people: nowhere would this be more true than in the West Midlands. Our demographic projections show that, unlike almost any other city-region in England, our working age population and its diversity is set to grow significantly over the next twenty years. Indeed, the growth in our population will be equivalent to welcoming in the current population of the city of Leicester.

The youthfulness and diversity of the West Midlands population will be its critical economic strength and driver of growth, but its true potential will only be unleashed if its people have the capacity to flourish. Our recent State of the Region report paints a challenging picture of the health and well-being of too many of our people with high levels 22 of child poverty, poor health and low educational attainment. Not only do these issues bring distress to those who suffer with them, they drag our economy back. They will be more fully addressed in Chapter 3.

More specifically, to unleash the economic potential of our region we need to address our high levels of youth unemployment, economic inactivity and relative lack of higher skills.

Youth Unemployment

In February 2025, there were 26,715 young people claiming out of work benefits. This represents 9.1% of the population aged 18-24 in the region, significantly higher than the national average of 5.5%. The youth claimant count has been rising in the region since mid- 2022. While this trend is observed in the national data, the increase in the WMCA area is greater and so the gap between the region and the national average is widening. Reducing the regional 18-24 claimant rate to the national average would result in over 10,000 fewer young people claiming out of work benefits.

The West Midlands Youth Employment Plan sets out the offer to young people to ensure they have the best possible start to their working lives through meaningful advice, support services and pathways, in addition to a commitment to creating 20,000 new work experience and training placements and apprenticeships by working with partners and businesses across the region. The WMCA would like to play a much bigger role in addressing education provision for 16-19 year olds.

Economic Inactivity and Under-employment

There are fewer economically active people in the region, our economic activity rate is 73.9%, compared to a national rate of 78.8% and 26.1% of our population are inactive (not seeking work or unable to start work), compared to the national average of 21.2%. If we were to reduce the share of the population in the region that are economically inactive to the national rate there would be more than 90,000 more economically active people in the region.

Much of the economic inactivity in the region is linked to ill health, with overall poorer outcomes for women, disabled people, ethnic minorities and our young people but the specific challenges facing the West Midlands—which account for our disproportionate levels of inactivity—are mainly related to the disproportionate number of women who are undertaking caring responsibilities. Overall, 122,000 people are economically inactive because of their caring responsibilities. Our challenges are compounded by the varying conditions across our diverse localities, which our Employment and Skills Strategy seeks to address.

There is also evidence of under-employment within minority ethnic groups in the region. Using a definition of underemployment as a lower level of actual employment for a particular ethnic group than predicted employment based on the employment rate by qualification and age across the population, it is estimated that in 2022 underemployment for minority ethnic groups was 38,300 (or 9%) lower than it would have been if employment rates by qualification matched the average. This too requires further concern and attention.

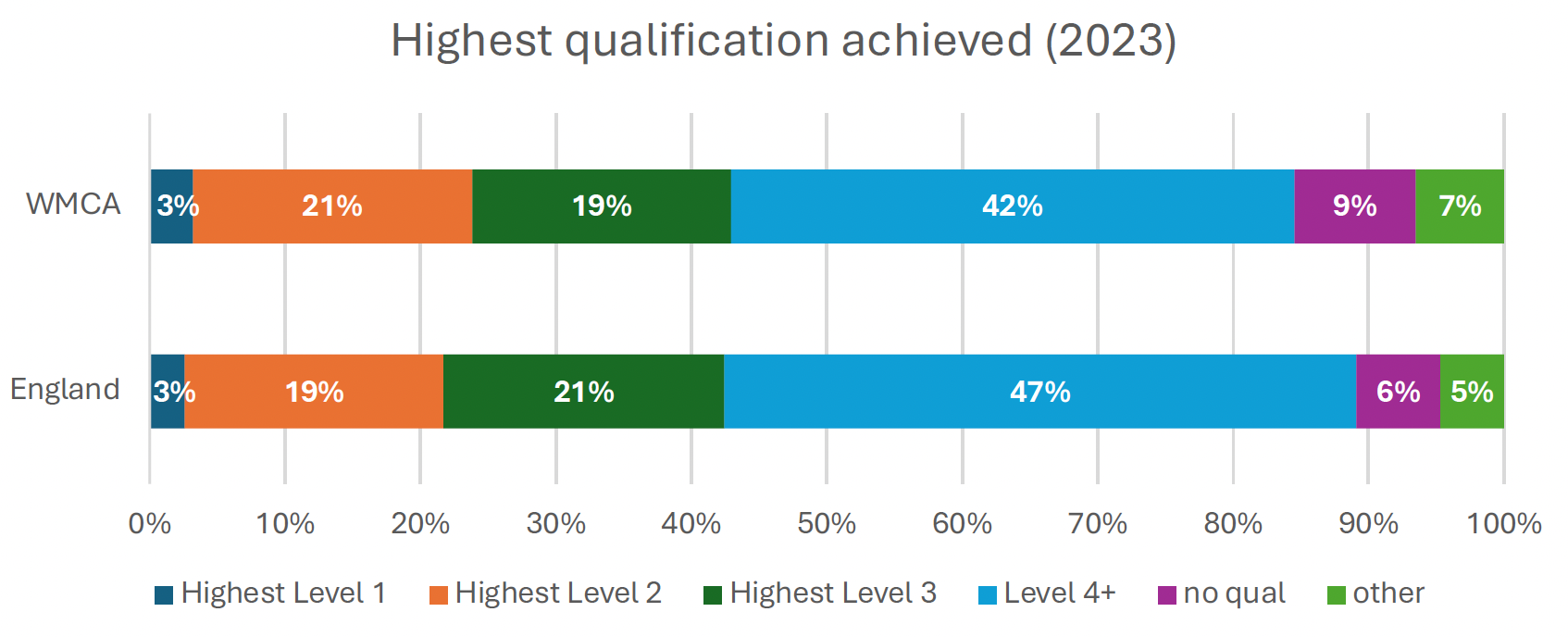

Qualifications and Higher Skills

The West Midlands is moving towards a high-skill economy. Over the last ten years the most significant increases in qualification levels have been at the graduate level (Level 4) as 23 well as Level 2 (GCSE level). Over the next ten years, by 2035, over half (55%) of the roles created in the WMCA area will be at Level 4 or above. Higher-level STEM skills in particular will unlock the next generation of new ideas and the ability of firms to convert new ideas into higher output and productivity.

Qualification levels are improving in the region; however, they remain lower than the national average. Around 1 in 10 adults in the WMCA area have no formal qualifications. 60.7% are qualified at Level 3 or above, compared with 67.8% nationally. As a result, employers face persistent skills shortages, with around 1 in 4 vacancies classed as ‘hard to fill’, particularly in roles that require advanced and/or higher skills. We could help meet these needs. If we were able to close the gap with the national average, there would be nearly 130,000 more residents in our region qualified at level 3 or above.

Figure 4: Bar chart showing highest qualifications achieved by residents of WMCA compared to England as a whole

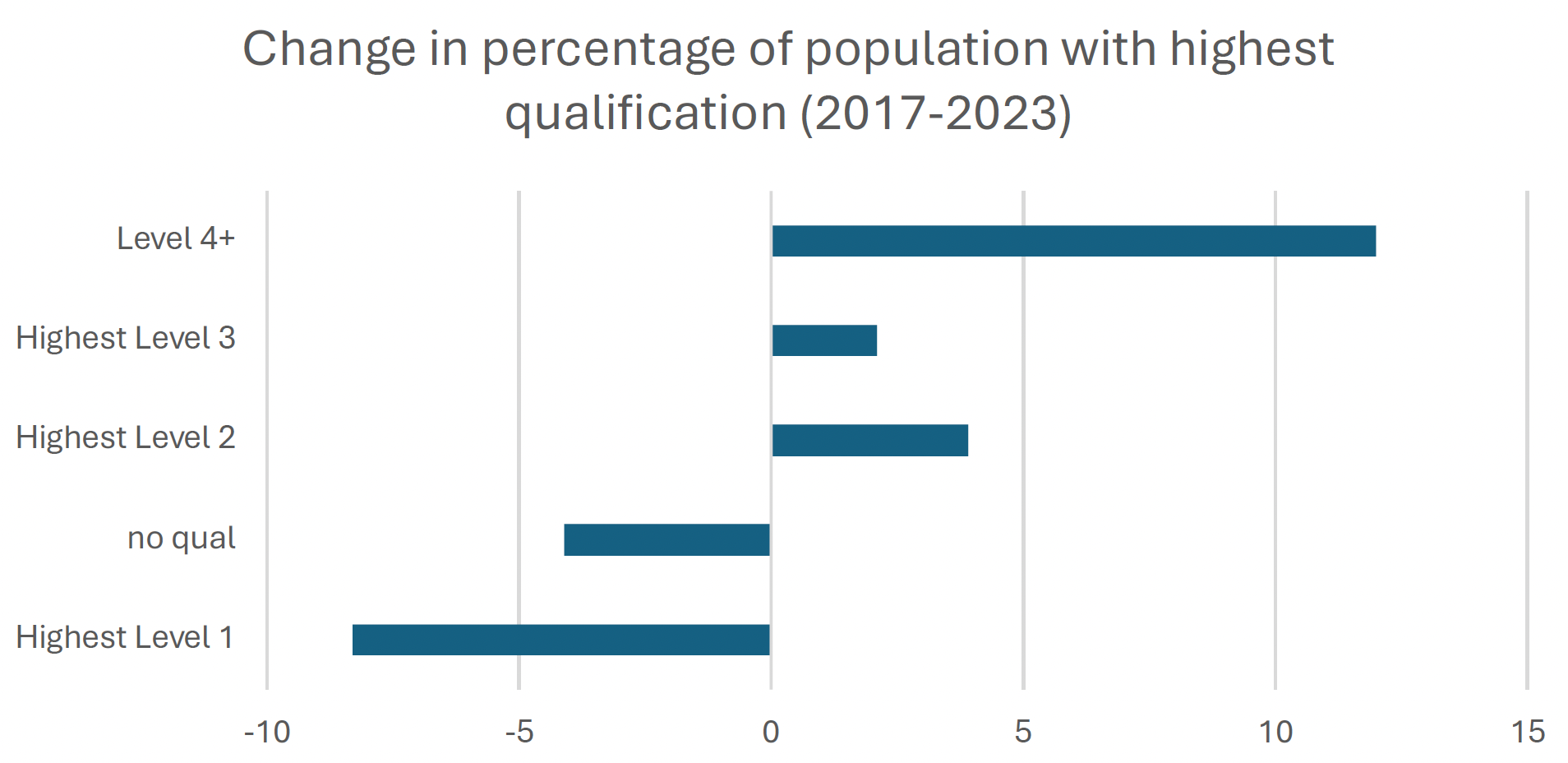

As illustrated overleaf in figure 5, over the last ten years the most significant increases in qualification levels have been at the graduate level (Level 4) as well as Level 2. However, the region has not been as successful in progression into Level 3 qualifications, in part due to lack of capacity in the skills system to provide access to technical provision which we have sought to increase since 2019. This lack of progression is an issue for employment and productivity in the region.

Figure 5: Bar chart showing change in percentage of population with highest qualification in the WMCA

Based on this analysis, we believe we need to put a particular focus on addressing the Level 3 qualifications gap.

As well as the relative gap, the reasons for this focus are as follows:

- Residents in the West Midlands with a level 3 qualification are more likely to be employed, earn more when employed, and less likely to claim out of work benefits than those qualified at level 2 or below.

- On average, residents in the West Midlands with level 3 qualifications achieve 16% more in earnings are 4% more likely to be employed than those with Level 2 and throughout their working lives are more resilient to labour market change.

- Level 3 skills are an important bridge to Level 4. As qualification attainment levels increase (L4+) so too the positive return. For example, Level 5 return for men is 21% and for women 29%.

- There is also strong and growing demand for higher-level skills (Level 3 and above) in the West Midlands.

Level 3 STEM skills are also vital for the generation of new ideas and the ability of firms to convert new ideas into higher output and productivity. There are similar links between a firm’s absorptive capacity to make the most of innovations and the workforce’s overall skills levels. This suggests that working with employers and their existing employees within firms in the region is crucially important.

STEM skills also provide a set of core skills which can be applied across various fields and industries, particularly in sectors and clusters which require green technologies and processes. Green skills are important in this respect because they increase the ability of firms in our region to adapt and take advantage of new growth and employment opportunities. Increasingly, green skills are understood to be crucial for resilience of firms across a wide range of sectors, in addition to traditional energy intensive industries.

Developing green skills of our current and future workforce is therefore important for both our achieving net zero ambitions as well as maximising growth and employment opportunities.

Outcomes

Over the coming ten years we will prioritise our collective efforts to:

- Tackle youth unemployment and the drivers of economic inactivity, with a particular focus on better supporting residents with caring responsibilities and addressing racial inequalities in the labour market.

- Equip our residents with the skills they need for a higher-skilled economy.

Questions

9) What more needs to be done to address our high levels of youth unemployment in the region?

10) How do we support more people into paid work?

11) Do you agree with the focus on Level 3 skills and how can we foster better engagement between businesses and skills providers?

6) Our Economic Networks and Narrative

Recent research by the Connected Places Catapult shows that the West Midlands is one of the top 100 global city-regions for its all-round performance when it comes to infrastructure, investment and institutions and it is in the top 250 in terms of global reach. But to sustain this position it must recognise the importance of better co-ordination and leadership across multiple local areas and a strong collective economic identity.

The research identifies a range of other forward-thinking city-regions from whom the West Midlands could learn and form effective partnerships and it points to this significant risks of regional fragmentation in an international marketplace where other city-regions are becoming increasingly adept at organising and presenting themselves as great places to live, work and invest.

Since the election of Mayor Richard Parker, a new emphasis has been placed on regional partnership working through the West Midlands Partnership Plan. Led by the local authority chief executives, this work is attempting to bring greater alignment between the activities of the different constituents making up the West Midlands Combined Authority. In parallel, a regional review of economic development functions has identified the need to enhance the role of the West Midlands Growth Company and form a new ‘economic delivery vehicle’ which will bring together activities such as business support, cluster development and investment and capital attraction.

There is also growing enthusiasm to enhance a clearer narrative about the West Midlands economy and its strengths to create a ‘story of place’ that is developed and amplified in culture and the media and shapes the way the region is perceived. Building upon the global reach of the Commonwealth Games in 2022 and the positive and distinctive image of the region that was projected through that event, the West Midlands has the opportunity – in part through its WM Growth Plan – to present a consistent image of a region that has shaped the global economy for over two centuries through being a crucible for change and innovation.

The West Midlands Growth Company’s 'It Starts Here' campaign – with its focus on the region’s innovation capabilities – has proved to be particularly compelling to date. It emphasises the importance of the region being home to the UK's fastest-growing tech sector, where the latest advancements are not just dreamt of, but made real; its network of top universities and research capabilities; and the pioneering businesses driving the cluster development highlighted in section 2.1 above.

But our growth narrative also needs to capture our wider strengths: our scale, location, youthfulness and diversity; and our cultural and creative life. Questions remain about branding and place recognition and how we better seize opportunities to develop ‘soft power’ on the national and global stage. Our West Midlands Growth Plan will be a fresh opportunity to tell a more coherent story of our place, its people and its economic opportunities and our ambition for change.

Outcomes

Over the coming ten years we will prioritise our collective efforts to:

- Strengthen the region’s institutions by forming more effective partnerships and enhancing the region’s approach to economic development delivery;

- Tell a new, confident narrative about the West Midlands, which shows up in stronger perceptions of the region by our key partners.

Questions

12) How should we improve the institutions and networks that support economic growth?

13) What makes the West Midlands economy special and how can we better speak with one voice in the region?